|

|

Revitalizing Indigenous Languages | |

| books | conference | articles | columns | contact | links | index | home | |

|

Chapter 7 of Revitalizing Indigenous Languages, edited by Jon

Reyhner, Gina Cantoni, Robert N. St. Clair, and Evangeline Parsons Yazzie

(pp. 84-102). Flagstaff, AZ: Northern Arizona University. Copyright

1999 by Northern Arizona University. Return to

Table of Contents

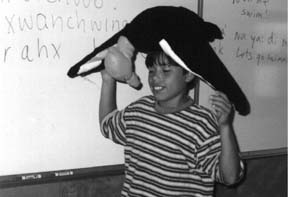

The Place of Writing in Preserving an Oral LanguageRuth Bennett, Pam Mattz, Silish Jackson, Harold CampbellThis paper shows how a traditional story can be used to teach an indigenous language and how the inclusion of writing can help students learn the language effectively. The Language Proficiency Method used by the Hoopa Valley Tribe's language programs is described along with supporting research and sample Hupa language activities built around the story "Coyote Steals Daylight." The activities demonstrate a sequencing principle basic to the method. They begin with questions and answers and progress to conversations, games, storytelling, and dramatic performances.This is the beginning of Xonteh This is a story about what Coyote did.Hupa teachers tell many Hupa stories to teach the Hupa language. The story Xonteh This story demonstrates the moral complexity of native California stories. One way to look at what Coyote does is that he brought something good to all the people. There is another side to this, however. Coyote takes daylight away from a house where it has been left with two children. He tricks two boys into getting some water for him, so he can escape with the bag of daylight. So, although Coyote's actions are good in one sense, in another sense they are ruthless. Coyote's actions in this story show his individualistic side; acting alone, Coyote runs with the bag of light, and even though he is caught, he brings daylight to the world. Hupa people have told Coyote stories for thousands of years. The characters' actions are sometimes humorous, sometimes serious. They record how the world that Indians know came to exist. Continuing to tell the old stories in the Hupa language preserves the native language for Hupa people and preserves their oral history. Creating Hupa story lessons provides a way to use stories in teaching (Wilkinson, 1998). Teaching stories effectively requires a method of presentation. In the Language Proficiency Method described in this paper, the focus is on a sequence whereby students can progress from easier to more difficult material. Language Proficiency units begin with lessons built around questions and answers and expand to conversations, games, storytelling, and dramatic performances. The writing activities described in Appendix B of this paper illustrate the Language Proficiency Method, which is used in the Hupa Language, Culture, and Education Program of the Hoopa Valley Tribe in a variety of classes, ranging from preschool through high school. Figure 1. Bishop Rivas and James Jackson, Hupa Language, Culture, and Education Program  The writing component in language lessons An important consideration in any language teaching method is to maximize opportunities for learning. In Hupa language classes, time is of the essence because Hupa, like many other indigenous languages, has few people left who speak it every day. In this situation, the native language is a second language for the students. Because the Hupa Language, Culture, and Education Program is a second language program, it is important to consider carefully various approaches for teaching second languages. One question that arises in second language teaching is whether to concentrate on speaking, or to also include writing. Critics of writing instruction maintain that students who spend too much time writing never learn to speak. These critics maintain that indigenous languages are complex and that learning a writing system only makes things more difficult. Writing instruction takes up time that is better spent speaking. Another argument in favor of teaching spoken language as opposed to written language is that Hupa and other California languages have become written languages only in this century. Their writing systems have been developed by scholars and so are not needed by native people (see Bielenberg, this volume). However, the complexity of the language can also be the basis of arguing for the use of writing in language lessons. Although historically the Hupa language was oral, its complexity includes a grammar where verb stems can change form from singular to plural. Its system of meaning is complex as well, with many words based upon metaphors that require interpretation of images. Writing down the forms of a complex language can be a way of dealing with these complexities so they can be better understood by students. Students need to return again and again to a form, and writing provides a ready reference. A second argument in favor of writing is that Native people have adopted writing systems for their languages in recent years (Hinton, 1994). In northwest California, the Hoopa Valley Tribe, the Karuk Tribe of California, the Wiyot Tribe, the Yurok Tribe and the Tolowa each have writing systems. The Language Proficiency Method Before explaining the Language Proficiency Method, we need to explain that there are a variety of names and other variations in this method, but the general principles have been advocated by various California programs, including the California Foreign Language Project--Redwood Area at Humboldt State University, the Native California Network (a privately funded Native American organization), a Karuk Language Conference Center in Orleans, and the Johnson-O'Malley Program of the Hoopa Valley Tribe. The Language Proficiency Method is based upon the belief that writing is useful within a program of language instruction. Writing offers a sequence for presenting new language material, moving from easier to harder forms, and can also be the basis for communication. When writing is included in the program, the teacher can move from speaking to reading and writing, reinforcing concepts with writing. The sequence in the method begins with attention-getting lesson presentations by the teacher. From level 2 through level 5, each level builds on the earlier one. A new level is introduced when students approach mastery at a given level. Teachers often ask at what level in the sequence to introduce writing. This choice is left to the teacher, although it is possible to introduce writing at beginning levels. The levels are as follows: 1. Setting the Scene: capturing attentionAt the first level, the student listens. At the second level, the student demonstrates understanding non-verbally. At the third level, the student responds with one or two word responses. The student formulates complete sentences in level 4. By level 5, students generate their own conversations (Bennett, 1997). The levels build from where the teacher talks to the students to where the students talk to each other. Each level consists of lessons that include culturally relevant activities. These range from a Hupa story told by the teacher to questions and answers about Hupa life, to games that involve play with cultural concepts, to student performances of Hupa plays (See Appendix B for sample activities for each level). Figure 2. Sarah Jarnaghan with Mina:xwe Raccoon Puppet

Issues relating to writing How writing is defined affects some issues related to written language instruction. These issues relate to the following: 1. the idea of writing as a learning toolWriting as a tool in learning: One issue involves a correspondence between learning to speak and learning to write. Writing in language programs has been criticized on the basis that students who learn to write well learn grammar rules and their spoken language suffers. It is important in native language programs that writing be a tool for improving speaking skills, not for replacing them. When presented as an option, writing can be a valuable tool both in enhancing group activities and in developing self-study skills. Teachers can convey the idea of writing as a tool by the type of activities they include in their lessons. They can ask students to write down what they hear, they can assign them to transcribe from tapes, and they can ask them to develop questions based upon readings. Learning to speak vs. learning to write: A second issue involving written language relates to what language is spoken in contrast to what is written. In one view, spoken language is broader than written language. In this view, spoken language is any utterance, but written language refers to forms of discourse. In this definition, the idea of written language places it on a different level from spoken language. This is based upon the fact that written language requires prior knowledge of a spelling system, grammar rules, and sentence patterns. Written language becomes associated with more advanced learning, and therefore with larger pieces of language, such as fiction, nonfiction, and other forms of discourse. This view of the difference between oral and written language makes the assumption that written language is "a higher level of language" (Cohen, 1997). This view of writing, however, can be counterproductive. When students feel that they have to adhere to a higher standard than they are capable of, they may give up altogether. The belief that written language can be anything that is spoken creates a liberated view of writing. In this view, written language encompasses all utterances, including colloquial expressions, one-word utterances, and even gasps and sighs; all of these spoken utterances can be written down. In this view, writing is speech written down. This view de-emphasizes the notion of correctness associated with written language in the other view. It is intended to encourage students to write, being aware of correctness but not repressed by it. It is important that writing be a tool to help the student. Writing connects to what is heard and spoken. The letters of an alphabet are a visual accompaniment to vowel and consonant sounds. A writing system is a way of making a spoken language tangible because it exists in a form where it can be collected, stored, and recalled. Learning response patterns: A third issue involving writing is related to second language learning and the nature of interpretation and translation processes. Ways of interpreting are based on prior experiences and upon shared knowledge with others who speak the language. When students begin learning a second language, they rely on ways of interpreting that have been acquired through their first language. They continue to use their first language in their interpretations until they develop sufficient patterns of response in a second language. It is generally known that learning how to write in a second language is a common obstacle encountered by language students. A reason for introducing writing early in the learning process is that when students become accustomed to writing in the second language, it is no longer an obstacle to be feared later on. In addition, early introduction of writing provides an opportunity for writing skills to develop simultaneously with new thought processes in the second language. Figure 3. Hupa Language, Culture, and Education Summer Program Student Portraying a California Condor  Research on learning styles and learning strategies: Various research studies have shown that instruction that combines writing with spoken language reaches a broader group of students. This is owing to differences in learning styles and learning strategies. Research on second language acquisition substantiates this view, showing that if a classroom inhibits students' opportunities to demonstrate their knowledge, learning will be affected (Johnson, 1995). A rationale for teaching writing is that some students are visual learners, rather than auditory. These students have difficulty grasping meanings from sounds. When writing is introduced to these students at the one-or-two word response level, these students especially benefit. Conversely, when writing is held off until these students are at the stage of communicating forms of discourse, they are slowed down more than other students as they translate, interpret, and remember more effectively with the assistance of writing. The Language Proficiency Method adapts readily to instruction in written language. Activities that incorporate writing proceed as follows (See Appendix B for sample writing activities for each level): 1.Setting the Scene: Teacher shows flashcards with pictures named in the native languageStrategies proven effective with Native American students: Research has shown that Native American students benefit from a variety of learning strategies--including social, cognitive, memory, and compensatory ones--and that learning styles influence learning strategy (Okada, Oxford, & Abo, 1996). Writing is particularly useful to students who have visual learning styles. Research on Native American students has dealt with various aspects of learning styles and learning strategies. A well-known study of Native American students' classroom learning was carried out by Susan Philips (1972) on the Warm Springs Indian Reservation. Philips compared differences between the social conditions governing verbal participation in middle-class Anglo-American classrooms and in the Warm Springs community. She found that the Warm Springs students' willingness to participate was related to the ways in which verbal interaction was organized and controlled. Philips' observations of Warm Springs students revealed that Warm Springs students were more willing to participate verbally when they could self-select when to speak. This was consistent with conditions within the Warm Springs community where learning tasks generally follow a sequence of extensive listening and watching, then supervised participation with tasks segmented by an elder, and then private-self-initiated self-testing of what is learned. The use of speech in such activities is minimal, and competence is demonstrated through the completion of the task itself. Philips argues that to accommodate children of different cultural backgrounds such as the Native American culture, "efforts be made to allow for a complementary diversity in the modes of communication through which learning and measurements of 'success' take place" (Philips, 1972, p. 393). In a 1997 article Heredia and Francis examine the instructional uses of traditional stories in realizing the educational potential of Native American children. They report that stories were the books for all Native American peoples. They state that it is important to understand that some tribes had writing systems before Europeans introduced alphabetic writing in the sixteenth century. Tribes already had various pictographic, iconic, and mnemonic systems related to their interest in storytelling as well as to the preservation of their languages over thousands of years. Because of the broad popularity of stories since intercultural contact, Heredia and Francis view stories as a potential for enriching the reading and language arts curriculum, with direct applicability to "developing students' writing skills" (1997, p. 53). In a study of the influence of stories on oral and written language development, Aronson shows that children who listen to stories learn that stories are a method of communication. "From stories children acquire expectations about the world. They learn about language and people and places" (1991, p. 12). The use of story conventions as an indication of language learning was found in children's written stories. Their language learning included knowledge of narrative conventions, such as formal beginnings, formal endings, and consistent uses of past tense. Research has shown that stories provide a narrative model for students' writing and are vital to their early language development. The use of story conventions were reported as early as age two when children are at a one-or-two word stage of oral language development. Aronson (1991) reported that children were writing stories by age five. In a study of Native American children on the Hoopa Valley Indian Reservation in California, Bennett (1980) demonstrated a progression in language development in children age 2 through 12. Proto-narratives appeared at the two-word stage, expanding in complexity as the children grew older. In documenting the role of stories in passing on the Native American heritage, Bennett demonstrated that the older children told traditional stories. These stories were composed with metaphorical interpretations and multi-sentence organization. Students benefited in classroom instruction from writing down stories they had heard. Earlier studies that demonstrate the importance of writing for Native American students document their visual learning styles. In a comparative study of Navajo children and Dutch whites in Michigan by Steggerda and Macomber (1934), Navajo children were found to perceive visual objects according to the usefulness in their visual context. The Navajo children rejected the horse that was old and thin, the landscape that had no water or shade, and the house with no room to walk around. The Dutch whites, in contrast, were aware of the objects as pictures, and noted form, arrangement, and colors. The conclusion is that the Navajo children read the stories told in the pictures to understand visual cues. The implications are both that the Navajo children are visual learners and that they use cultural forms of language, such as stories, to interpret visual cues.

Figure 4. Icha Little, Charlotte Saxon, Silish Jackson (back),

Keweah Rivas (front), Angela Saxon, Laura Del Santos, and Danny

Ammon Performing Xa:xowilwa:t  In a classic study comparing Native American children with Euro-American children, Wayne Dennis (1942) tested visual perceptions in a Draw-A-Man test. The drawings of Hopi children in the older age group (age 10 as compared with age 6) showed more cultural traits, with the drawings showing Hopi hairstyles and dress, including ceremonial dancers. Hopi children reflect their cultural experiences in their drawings. The conclusion is that writing (in the form of drawing) is an important part of the language development that appears in the youngest children in the study and shows an increase in socio-differentiation with age. This study documents the cultural basis for visual learning. The success of writing activities introduced in Native American language classrooms depends upon students finding themselves in instructional situations that they recognize. Johnson (1995) showed that it is crucial for the teacher to become established as a socially relevant figure whose approval is valued by the students. How the teacher accomplishes this task includes the use of visual aides. Flashcards, puppets, and other aids play a role in having students perceive the teacher as someone who reaches out to them. Tasks need to be designed so that students can succeed and teachers have the opportunity to give approval to correct student responses. Thus, it is important not to introduce writing at too early an age or to let writing substitute for speaking. The sequencing of units as well as the amount of material students can assimilate are other important issues (Geerbault, 1997). Below is a checklist for writing activities and a list of advantages and disadvantages: students practice writing the letters that represent each of the soundsConclusion: Meeting the needs of the Hupa community At the time the Hupa Language, Culture, and Education Program began in 1963, there were monolingual Hupa speakers. These people were so immersed in the Hupa language and culture that they lived entirely on the 12 square miles of the Hoopa Indian Reservation. At this time, the Hupa oral tradition was a part of the daily life of people living on the reservation. It was possible to visit an elder's home and hear a story handed down from the ancestors, much as it had been for thousands of years previously. Today, Hupa language elders are bilingual. Some have traveled to other countries, and many have communicated with people from other continents. Today's Hupa language students live in a global community as well. They participate in electronic networking that includes e-mail, the internet, interactive videos and CD's, and extends worldwide. Rather than decrease the value of the Hupa language, however, the worldwide basis for communication has increased it. For the Hupa language students, study of the Hupa language enlarges their range of communication. There is interest in the Hupa language by many from outside the community. Bilingual skills enable Hupa speakers to share their language as a way of participating in international discussions. Figure 5. Community Hupa Language Class: Front Row: Tasha Norton, Minnie McWilliams, Jill Sherman, Cody Fletcher, Nina Kebric, Lila Kebric, Natalie Carpenter, James Jackson, Calvin Carpenter. Back Row: Myra Kebric, Gina Campbell, Danielle Vigil, Wendy George, Jacqueline Martins, Gordon Bussell, Melody Carpenter, Joseph Rafael, Marcellene Norton, André Kebric, Visiting Professor from Moscow, Russia  Figure 6. Pam Mattz, Director, Hupa Language, Culture, and Education Program, and Gordon Bussell, Hupa Language, Culture, and Education Program Teacher, Examining Acorn Paddles Made by Johnson-O'Malley Program Students

Note: Photos: by Ruth Bennett; Graphics: Photo-scans by Kelly Getz, CICD Graphics Dept. References Adley-SantaMaria, Bernadette. (1997). White Mountain Apache language: Issues in language shift, textbook development and Native speaker-university collaboration, Jon Reyhner (Ed.), Teaching indigenous languages (pp. 129-143). Flagstaff, AZ: Northern Arizona University. Aronson, Roxanne. (1991). The impact of literature on oral and written language development. Unpublished master's thesis. Sioux Falls College, SD. Bennett, Ruth. (1980). Hoopa children's storytelling. Unpublished doctoral dissertation, University of California, Berkeley. Bennett, Ruth. (1997). It really works: Cultural communication proficiency. In Jon Reyhner (Ed.), Teaching indigenous languages. (pp. 158-205). Flagstaff, AZ: Northern Arizona University. Cohen, M.D. (1997). California foreign language project: Redwood area. Unpublished manuscript Humboldt State University, Arcata, CA. Dennis, Wayne. (1942). The performance of Hopi children on the Goodenough Draw-A-Man Test." Journal of Comparative Psychology, 34(3), 341-348. Gerbault, Jeannine. (1997). Pedagogical aspects of vernacular literacy. Andree Tabouret-Keller, et al. (Eds.), Vernacular literacy: A re-evaluation. Oxford, UK: Clarendon. Gifford, E.W. (1930). California Indian nights. Lincoln: University of Nebraska. Heredia, Armando, & Francis, Norbert. (1997). Coyote as reading teacher: Oral tradition in the classroom. In Jon Reyhner (Ed.), Teaching indigenous languages (pp. 46-55). Flagstaff, AZ: Northern Arizona University. Hinton, Leanne. (1994). Writing systems. In L. Hinton, Flutes of fire: Essays on California Indian languages (pp. 211-219). Berkeley, CA: Heyday. Johnson, Karen. (1995). Understanding communication in second language classrooms. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University. Okada, Mayumi; Oxford, Rebecca, & Abo, Suzuna. (1996) Not all alike: Motivation and learning strategies among students of Japanese and Spanish in an exploratory study. In Rebecca Oxford (Ed.), Language learning motivation: Pathways to the new century (pp. 105-120) Honolulu, HI: University of Hawaii at Manoa. Philips, Linda M. (1989). Using children's literature to foster written language development (Tech. Rep. No. 446). Center for the Study of Reading, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. Philips, Susan. (1972). Participant structures and communicative competence: Warm Springs children in community and classroom. In Courtney Cazden, Vera John, & Dell Hymes (Eds.), Function of language in the classroom (pp. 378-387). New York: Teachers College. Steggerda, Morris, & Eileen Macomber. (1934). A revision of the McAdory Art Test applied to American Indians, Dutch whites and college graduates. Journal of Comparative Psychology, 26, 349-353. Wilkinson, Leona. Native California Network, oral communication, 5/5/98. Appendix A

This is a story about what Coyote did. Coyote was walking along. And then he saw some people digging Indian potatoes. But it was still dark yet, there wasn't any daylight. When the people saw Coyote, they said, "Come on up to the house." Coyote was surprised to see a building, a big long house. There weren't very many long houses around there, so he became curious. He decided to go up to the long house. And then when he got there, Coyote saw two little boys sitting in that house. And then Coyote went inside the house and looked around. He saw a lot of things hanging up there next to the roof. And then he looked up at the bags and asked the two boys, "What is that?" They told him that they didn't know. Then, when Coyote kept on asking them, one of them said, "Look, that bag there is only rain. That other one there is lightning." Now Coyote was really curious. He noticed that one of the bags was bigger than the others. Coyote asked, "What is that big bag for?" Coyote kept on asking about each one of the bags. Then, he saw a bag that was bigger than the others. He had to know what that one was, so he asked, "What's in that bag?" The boys kept silent, but finally one of the boys told him, "That one is daylight." And then when Coyote found out that Daylight was in that bag, he thought, "I am going to steal that bag with Daylight in it." He told those two boys, "Bring some water for me." When they went off, he thought, "I hope you will be gone a long time." He wanted them to stay away from the house. If only they would start playing, they might stay away longer, he thought. That big bag was hanging up. Coyote knew he had to act quickly. And then he jumped up; he grabbed that bag. He jumped up and brought the bag down from the rafters. He ran away fast with that big bag. And then he ran away fast with it all. And then those two boys came back. They went into the house. And then they looked inside. That big bag wasn't hanging there any more. They looked; that big bag that used to be hanging there was gone. He stole that daylight. Yes he did. And then the two boys ran off. They were chasing Coyote. "Come back here," one of them shouted to Coyote. "You stole Daylight from us." But Coyote didn't stop. And then one of the boys said, "We'll have to bring in the fastest birds: Hummingbird, grouse, pigeon." That's some of the fastest ones, they had to bring in the fastest birds to catch Coyote. And the two boys kept on looking for Coyote. Then they came across a house. There was an old man sitting in front of the house. He was someone who looked like a rich man. He looked like he had been sitting there for a long time. So they thought, "Maybe this is his house." They asked him, ""Haven't you seen coyote? He stole daylight from us." The old man said, "No." Outside the house, there was a flat rock. Just then, the boys saw Coyote running around in back of the house. The boys knew that the old man had turned into Coyote. They ran to tell the birds, "We know where Coyote is." Those birds flew after him. And then they caught him. And then they picked him up. They told him, "Bring that bag of daylight back." As they were carrying him, he was still holding the bag. He brought it back out. And then Coyote threw the bag down on a rock. The bag of daylight fell down on the rock. It broke the bag. Daylight went everywhere. When he broke the bag, Daylight came to be. He did it, he brought the daylight. That's the end of it. Writing Activities at Six Levels with Sample Hupa Language Activities Built Around the Story "Coyote Steals Daylight" 1. Setting the Scene a. teacher creates the context, relates the task to student interests2. Comprehensible Input 3. Guided Practice a. Teacher asks student to respond to either-or questions4. Independent Practice Student supplies vocabulary term5. Challenge 6. Expansion Expansion activities are based on comparisons with what has been taught in a lesson and involve looking at the story in a different way. This can be as brief as comparing one story with another or as lengthy as a series of lessons comparing versions of a story throughout the oral tradition of many tribes. Many tribes have stories about the coming of fire or daylight. Some tribes visualize both arriving with the coming of the sun. The California stories usually start with a state of unrest where people are in the dark and cold. Then someone is found to have daylight or fire. Coyote frequently, although not always, is the one who makes the attempt to get daylight or fire. Sometimes he steals it by himself, as in the Hupa Coyote Steals Daylight story. Sometimes he delegates this task to various animals, as in the Karuk story Coyote Steals Fire. In most versions of the story, this attempt is successful, and fire or daylight comes to the tribe (Gifford, 1930). Coyote's role in stealing fire or daylight is typical of his importance in the stories of northern California. Even when other animal characters are the main characters of a story, Coyote is likely to appear. When Coyote breaks taboos, he is often an object of humor, and an example to listeners of tribal standards of behavior. Usually he is portrayed as a male, with his roles ranging from creator to trickster, from buffoon to glutton. Sometimes Coyote's excesses turn to good ends, as when he steals daylight and brings it to the world. He appealed to California storytellers because of the diverse possibilities of his character to demonstrate both the good and the bad and to turn a misdeed into a change in nature that prepares the world for human beings. Stories by tribe from Northern California and Hawaii, about stealing daylight, fire, and/or sun, are given below: Cahto Goddard, P.E. (1907-10). The securing of light (1st version) by Bill Ray, The securing of light (2nd version) by Bill Ray, The stealing of fire by Bill Ray. Cahto Texts. University of California Publications in American Archaeology and Ethnology, 5, 96-102. Gifford, E.W., & Block, G. H. (1990). Stealing of the sun, by the Kato (Cahto) Indians of Mendocino County. In Albert L. Hurtado (Ed.), California Indian nights (pp. 153-154). Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska. Hupa/Chilula Bennett, Ruth. (1983). Coyote steals daylight--Fred Davis, James Jackson, Ruel Leach, Herman Sherman. Ethnographic transcripts, 529a-hl, 529b-hl, 6-23-83 (translation of Hupa text), 785b-hl, 2-17-84(English). Hawai'i Beckwith, Martha, (Ed.). (1970). Snaring the sun, Maui the trickster. In M. Beckwith, Hawaiian mythology (pp. 229-231). Honolulu: University of Hawaii. Karuk Bennett, Ruth, & Richardson, Nancy. (1984). Coyote steals fire by Julia Starritt, retold by Shan Davis. In Pikwa Stories. Center for Indian Community Development, ms. from William Bright, Karok Language, UCB, 1957. Kroeber, A.L. (Ed.). (1980). Coyote steals light, by Dick Richard's father-in-law. Karok myths (p. 61). Berkeley, CA: University of California. Fisher, Anne B. (1957). How animals brought fire to man. In A. B. Fisher, Stories California Indians told (pp. 46-53). Berkeley, Ca: Parnassus. Maidu Gifford, E.W., & Block, G.H. (1990). Mouse regains fire, by the Northeast Maidu Indians of Plumas County. In Albert L. Hurtado (Ed.), California Indian nights. (pp. 136-138). Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska. Miwok Curry, Jane Louise. (1987) Mole and the sun. In Back in the beforetime (p. 89). New York: Margaret K. McElderry. Northern Paiute Kelly, Isabel T. (Ed.). (1938). Coyote shoots the night. Northern Paiute tales. Journal of American Folklore, 51, 420-21. Owens Valley Paiute Steward, Julian H. (1932). Origin of fire, cottontail and the sun: Myths of the Owens Valley Paiute. University of California Publications in American Archaeology and Ethnology, 34 (5), 370-71 Pomo Barrett, Samuel A. (1940). Coyote creates sun and moon, by (Pakokota,) Northern Pomo born at Shorakai, Coyote Valley, on the East Fork of the Russian River. In Samuel Barrett (Ed.), Pomo myths, Bulletin of the Public Museum of the City of Milwaukee, 15, 141-147. Shasta Gifford, Edward W., Block, G.H. (1990). How coyote stole the fire, by the Shasta Indians of Siskiyou County. In California Indian nights (pp. 139-141). Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska. Tolowa Goddard, Pliny E. (1902-11). Recovery of the sun, origin of fire. In P.E. Goddard, Tolowa tales and texts. Unpublished manuscript, Museum of Anthropological Archives, University of California Berkeley. Wailaki Curtis, Edward S. (Ed.). (1924). Coyote provides daylight by North Fork John (Nahlse (sitting around), Eel River Wailaki. In The North American Indian (Vol. XIV) (p. 167). New York: Johnson Reprint. Yana Gifford, Edward W., & Block, G.H. (1990). How people got fire, by the Central Yana Indians of Shasta County. In Albert L. Hurtado (Ed.), California Indian nights (pp. 191-132). Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska. Yokut Curtis, Edward S. (Ed.). (1924). Coyote steals the morning star, by Dick Neale, Chukchansi Yokut. In Edward S. Curtis (Ed.), The North American Indian. (Vol. XIV) (p. 167). New York: Johnson Reprint. Yuki Curtis, Edward W. (1924). Fire is stolen from spider, by a Round Valley Yuki. In Edward S. Curtis (Ed.), The North American Indian (Vol. XIV) (p. 167). New York: Johnson Reprint. Yurok Kroeber, A.L. (1976). Grown in a basket by Lame Billy of Weitchpec (Coyote kills the sun and Raccoon restores him, e-k), Theft of fire by Billy Werk of Weitspus. In Yurok Myths (pp. 89-94, 237-244). Berkeley, CA: University of California. |

| books | conference | articles | columns | contact | links | index | home |

| Copyright © 2003 Northern Arizona University, All rights Reserved |