Faculty teaching online courses frequently ask us about using a proctoring tool to monitor students during exams in online courses because they have concerns about academic integrity. While it is true that live proctoring is somewhat effective at preventing students from cheating on a remotely administered exam, we believe that there are better alternatives. There are disadvantages to proctoring too, including the cost which, because of AZ Regents and NAU policy, must now be absorbed by departments rather that applied to students. Concerns are also arising around student privacy related to room scans, and there has been at least one legal ruling in favor of the students. It's also good to remember that these technologies are not even close to 100% effective at stopping cheating, so putting one's faith in them is a bit naive. We understand that proctored capstone exams are required for accreditation in certain programs, so the tools are available. But we don't recommend this approach in most cases.

Exams that use multiple choice, true/false, matching, and fill in the blank questions are popular with instructors, particularly in high enrollment classes, because they can be machine graded and the results are instantaneously available in the LMS's gradebook. They are easy to grade because the questions have discrete right and wrong answers. Machines are good at handling that. No judgment or thinking is required. The ability to administer machine graded, memorization-heavy exams allows the callous or the uninformed to say that enrollment in an online class can therefore be unlimited. However, that would only be true if we didn't care about quality. We know that students gain little from courses where all they must do to succeed is regurgitate memorized facts on an objective test. We know that courses without regular and substantive engagement between instructor and students, essentially online correspondence courses, have dismal success rates. There's a reason nobody's talking about MOOCs anymore. We've tried them. They didn't work. It's certainly ok to use low-stakes multiple choice quizzes to perform regular checks for comprehension, but they shouldn't be the primary means of assessment. It is not impossible to write multiple choice questions that engage critical thinking skills, but it's very difficult. Maybe we should do a workshop on that?

We can use Blackboard to make it harder to cheat on these kinds of tests, by randomizing question order and answer choices, by using question pools (so that each student gets a random draw of questions from a larger set). With math problems, we can have the software randomly input the values for the variables within a set of boundaries (for example, you could set x as a number between 3 and 8, and y as a number between 6 and 14), so that the problem, "x+y=__" results in a wide range of combinations while remaining, essentially, the same problem. However, all of this can still be cheated in an unproctored environment unless time is short, and tight time constraints can create issues for students with certain disabilities.

There is no technology that can prevent students from cheating on memorization-heavy exams. In fact, students are more prone to cheat on these types of exams because looking up facts is fast and easy, and because memorizing facts is hard. If the tests are high-stakes, that only exacerbates the problem. We also know from experience that once instructors get these exam questions up into the LMS, they rarely change them. Students have figured this out, and have developed a variety of counter-measures, including answer-sharing "study sites" like Chegg and CourseHero.

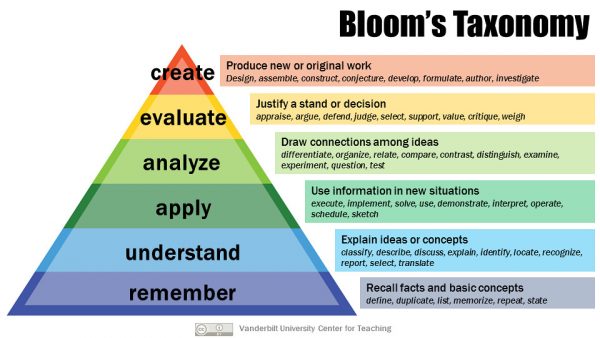

These types of tests only assess how many facts students can cram into their brains for the brief period between study and exam. Long-term retention of memorized facts is low, and understanding of what the concepts mean is generally lacking. Unless those crammed facts are used on a regular basis, they won't get stored in long-term memory. Instructors regularly complain that students fail to apply their knowledge to solve a novel problem, and that they lack the ability to draw connections, think critically, to analyze information, justify a position in a debate, or use their existing knowledge to develop original ideas. We can't blame this entirely on the students. They have adapted their study methods to optimize their performance on the kinds of tests we most commonly give them. And, for the rare instructor who is challenging students to think critically, students don't know how to study for that. The students desperately make more flash cards to memorize, and it doesn't help, because they don't understand the material.

So, while proctoring addresses the cheating problem, maybe it allows us to remain in denial about the bigger problem of continuing to rely on ineffective assessments.

Let's do a little demonstration to make the point. First, take a minute to memorize the six words shown in the pyramid above. Now step away from the screen, go do something else for five minutes, and then write them down in the correct order. How did you do? Probably ok. After all, you're a college professor! Next, read the text in the boxes to the right of the pyramid, and just think about how you would explain the levels of Bloom's taxonomy to someone who had never heard of it. Which was easier? Which has more lasting value?

Our best advice is to change the type of assessments, so that cheating is not so easy and more creative thinking is encouraged. Ideally, what we’d like to ensure is that the higher levels of Bloom’s Taxonomy are being addressed, because those are the useful life skills that go beyond the course. The “base level” skills are still necessary, but we should test on higher level skills. If students are lacking the base skills, they won’t be able to function at the higher levels. Students will actually enjoy these assessments more than memorizing, because people are good at pattern recognition, problem solving, finding connections; especially if we train them for it.

What we want is people who can apply their knowledge to analyze data, evaluate the quality of information sources, apply what they know, synthesize information, and come up with new ideas. In a math class, the "show your work" approach is better than the “did they get the right answer” approach. It takes more time to fake that.

Apply: If a student can apply their knowledge to a type of problem they’ve never encountered, that’s not easily cheated. Let them use any resources they have available. But ask them to explain their work.

Analyze: Analysis of graphs or data sets is also good, because it’s the interpretation of the data that shows what you know, and the answer can’t be googled.

Evaluate: Word problems are good because it’s the method you choose to solving it that matters, and there may be more than one way to get the right answer.

Create: Problem-based and project based learning are also good, because math is applied to a problem, but there can be more creativity in the approach. And with this kind of learning, the assessment might even be an interview where the instructor asks questions on the spot about the product the students produced. This work can be done in groups, reducing the grading effort. (We have suggestions on how to keep group work equitable too!). This interview method is also a good check against contract cheating, where a student hires someone to do the work for them. They won't get far if you ask a few probing questions.

Of course, faculty are correct that this kind of assessment, while better, is more work to grade, and the effort increases with class size. But using available funds to reduce class sizes is a better investment that proctoring, assuming that the instructor engages with the students. In a machine graded exam, with questions that rely on rote memorization, the class size can be almost unlimited and it’s no more effort, but getting a good grade on such an exam has little value. Ultimately we need to recognize that cheating will be attempted by some students no matter what we do, and the very best we can do is make it more rewarding for them to use their brains. We live in a world rich in information, but some of that information is hard to understand, and there's a lot of wrong or misleading information out there too. We shouldn't deny them access to it. But we need them to be able to sift through it, evaluate it, critique it, apply it to their problems, and do creative work.