|

|||||

| |

|

|

|

|

|

Obtaining an accurate history is the critical first step in determining the etiology of a patient's problem. A large percentage of the time, you will actually be able make a diagnosis based on the history alone. The value of the history, of course, will depend on your ability to elicit relevant information. Your sense of what constitutes important data will grow exponentially in the coming years as you gain a greater understanding of the pathophysiology of disease through increased exposure to patients and illness. However, you are already in possession of the tools that will enable you to obtain a good history. That is, an ability to listen and ask common-sense questions that help define the nature of a particular problem. It does not take a vast, sophisticated fund of knowledge to successfully interview a patient. In fact seasoned physicians often lose site of this important point, placing too much emphasis on the use of testing while failing to take the time to listen to their patients. Successful interviewing is for the most part dependent upon your already well developed communication skills.

What follows is a framework for approaching patient complaints in a problem oriented fashion. The patient initiates this process by describing a symptom. It falls to you to take that information and use it as a springboard for additional questioning that will help to identify the root cause of the problem. Note that this is different from trying to identify disease states which might exist yet do not generate overt symptoms. To uncover these issues requires an extensive "Review Of Systems" (a.k.a. ROS). Generally, this consists of a list of questions grouped according to organ system and designed to identify disease within that area. For example, a review of systems for respiratory illnesses would include: Do you have a cough? If so, is it productive of sputum? Do you feel short of breath when you walk? etc. In a practical sense, it is not necessary to memorize an extensive ROS question list. Rather, you will have an opportunity to learn the relevant questions that uncover organ dysfunction when you review the physical exam for each system individually. In this way, the ROS will be given some context, increasing the likelihood that you will actually remember the relevant questions.

The patient's reason for presenting to the clinician is usually referred to as the "Chief Complaint." Perhaps a less pejorative/more accurate nomenclature would be to identify this as their area of "Chief Concern."

Getting Started:

Always introduce yourself to the patient. Then try to make the environment as private and free of distractions as possible. This may be difficult depending on where the interview is taking place. The emergency room or a non-private patient room are notoriously difficult spots. Do the best that you can and feel free to be creative. If the room is crowded, it's OK to try and find alternate sites for the interview. It's also acceptable to politely ask visitors to leave so that you can have some privacy.

If possible, sit down next to the patient while conducting the interview. Remove any physical barriers that stand between yourself and the interviewee (e.g. put down the side rail so that your view of one another is unimpeded... though make sure to put it back up at the conclusion of the interview). These simple maneuvers help to put you and the patient on equal footing. Furthermore, they enhance the notion that you are completely focused on them. You can either disarm or build walls through the speech, posture and body language that you adopt. Recognize the power of these cues and the impact that they can have on the interview. While there is no way of creating instant intimacy and rapport, paying attention to what may seem like rather small details as well as always showing kindness and respect can go a long way towards creating an environment that will facilitate the exchange of useful information.

If the interview is being conducted in an outpatient setting, it is probably better to allow the patient to wear their own clothing while you chat with them. At the conclusion of your discussion, provide them with a gown and leave the room while they undress in preparation for the physical exam.

Initial Question(s):

Ideally, you would like to hear the patient describe the problem in their own words. Open ended questions are a good way to get the ball rolling. These include: "What brings your here? How can I help you? What seems to be the problem?" Push them to be as descriptive as possible. While it's simplest to focus on a single, dominant problem, patients occasionally identify more then one issue that they wish to address. When this occurs, explore each one individually using the strategy described below.

Follow-up Questions:

There is no single best way to question a patient. Successful interviewing requires that you avoid medical terminology and make use of a descriptive language that is familiar to them. There are several broad questions which are applicable to any complaint. These include:

The content of subsequent questions will depend both on what you uncover and your knowledge base/understanding of patients and their illnesses. If, for example, the patient's initial complaint was chest pain you might have uncovered the following by using the above questions:

The pain began 1 month ago and only occurs with activity. It rapidly goes away with rest. When it does occur, it is a steady pressure focused on the center of the chest that is roughly a 5 (on a scale of 1 to 10). Over the last week, it has happened 6 times while in the first week it happened only once. The patient has never experienced anything like this previously and has not mentioned this problem to anyone else prior to meeting with you. As yet, they have employed no specific therapy.

This is quite a lot of information. However, if you were not aware that coronary-based ischemia causes a symptom complex identical to what the patient is describing, you would have no idea what further questions to ask. That's OK. With additional experience, exposure, and knowledge you will learn the appropriate settings for particular lines of questioning. When clinicians obtain a history, they are continually generating differential diagnoses in their minds, allowing the patient's answers to direct the logical use of additional questions. With each step, the list of probable diagnoses is pared down until a few likely choices are left from what was once a long list of possibilities. Perhaps an easy way to understand this would be to think of the patient problem as a Windows-Based computer program. The patient tells you a symptom. You click on this symptom and a list of general questions appears. The patient then responds to these questions. You click on these responses and... blank screen. No problem. As yet, you do not have the clinical knowledge base to know what questions to ask next. With time and experience you will be able to click on the patient's response and generate a list of additional appropriate questions. In the previous patient with chest pain, you will learn that this patient's story is very consistent with significant, symptomatic coronary artery disease. As such, you would ask follow-up questions that help to define a cardiac basis for this complaint (e.g. history of past myocardial infarctions, risk factors for coronary disease, etc.). You'd also be aware that other disease states (e.g. emphysema) might cause similar symptoms and would therefore ask questions that could lend support to these possible diagnoses (e.g. history of smoking or wheezing). At the completion of the HPI, you should have a pretty good idea as to the likely cause of a patient's problem. You may then focus your exam on the search for physical signs that would lend support to your working diagnosis and help direct you in the rational use of adjuvant testing.

Recognizing symptoms/responses that demand an urgent assessment (e.g. crushing chest pain) vs. those that can be handled in a more leisurely fashion (e.g. fatigue) will come with time and experience. All patient complaints merit careful consideration. Some, however, require time to play out, allowing them to either become "a something" (a recognizable clinical entity) or "a nothing," and simply fade away. Clinicians are constantly on the look-out for markers of underlying illness, historical points which might increase their suspicion for the existence of an underlying disease process. For example, a patient who does not usually seek medical attention yet presents with a new, specific complaint merits a particularly careful evaluation. More often, however, the challenge lies in having the discipline to continually re-consider the diagnostic possibilities in a patient with multiple, chronic complaints who presents with a variation of his/her "usual" symptom complex.

You will undoubtedly forget to ask certain questions, requiring a return visit to the patient's bedside to ask, "Just one more thing." Don't worry, this happens to everyone! You'll get more efficient with practice.

Dealing With Your Own Discomfort:

Many of you will feel uncomfortable with the patient interview. This process is, by its very nature, highly intrusive. The patient has been stripped, both literally and figuratively, of the layers that protect them from the physical and psychological probes of the outside world. Furthermore, in order to be successful, you must ask in-depth, intimate questions of a person with whom you essentially have no relationship. This is completely at odds with your normal day to day interactions. There is no way to proceed without asking questions, peering into the life of an otherwise complete stranger. This can, however, be done in a way that maintains respect for the patient's dignity and privacy. In fact, at this stage of your careers, you perhaps have an advantage over more experienced providers as you are hyper-aware that this is not a natural environment. Many physicians become immune to the sense that they are violating a patient's personal space and can thoughtlessly over step boundaries. Avoiding this is not an easy task. Listen and respond appropriately to the internal warnings that help to sculpt your normal interactions.

![]()

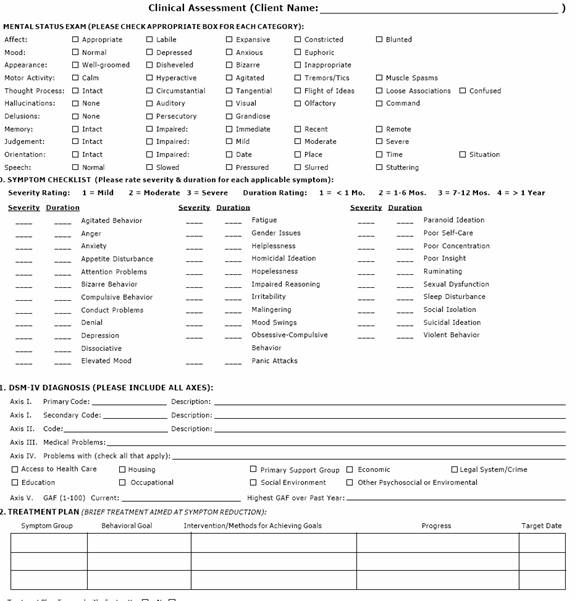

Next is an example of how a mental status exam is conducted:

In actual practice, providers (with the exception of a psychiatrist or neurologist) do not regularly perform an examination explicitly designed to assess a patient's mental status. During the course of the normal interview, most of the information relevant to this assessment is obtained indirectly. This review provides an opportunity to consciously think of the elements contained within the MSE.

In the day to day practice of medicine (and, in fact, throughout all of our interactions) we continually come into contact with persons who have significantly impaired cognitive abilities, altered capacity for memory, disordered thought processes and otherwise abnormal mental status. First and foremost, the goal is to be able to note when these abnormalities exist (you'd be surprised at how frequently they can be missed) and then to categorize them as specifically as possible. If a person seems "odd, confused or not quite right" what do we mean by this? What about their behavior, appearance, speech, etc. has lead us to these conclusions? In some instances, the patient's condition (e.g. markedly depressed level of consciousness, intoxication) will preclude a complete, ordered evaluation of mental status, so flexibility is important. Knowing when to "cut your losses" and abandon a more detailed examination obviously takes a bit of experience! The formulation of actual diagnoses, the final step in this process is, for the most part, beyond the scope of this discussion (I've included two of the most commonly encountered ones at the end of this section as examples). In fact, even if you had the experience and knowledge to generate diagnoses, this still may not be possible after a single patient encounter. The interview provides a "snap shot" of the patient, a picture of them as they exist at one point in time. Frequently, and this applies to the physical examination as well, several interactions are required along with information about the patient's usual level of function before you can come to any meaningful conclusions about their current condition. The components of the MSE are as follows: