|

It Starts with a Question. It Starts with a Question.

Ah, the classic question! "What is research?!"

- In education, as in all other topic areas, the key thing to remember is: IT ALL STARTS WITH A QUESTION! (need to know, curiosity, etc., etc.!)

- if it is in a question form, we call it a research question: e.g., "What is the relationship between motivation to teach and satisfaction level as a first-year teacher?"

- if it is in a declarative sentence form, we call it a problem statement: e.g., "This study is to determine the relationship between motivation to teach and satisfaction level as a first-year teacher."

- I consider the above two forms to be EQUIVALENT and leave it up to YOU as to which way you'd prefer to state your "curiosity." But some professors (and particularly, your dissertation chair) may have a preference as to one form or the other. Guess the moral is: "Know thy audience (and act accordingly)!"

- P.S. As a result of my own non-preference, I'll go ahead & use the terms interchangeably; e.g., "answering your research question(s)," vs. "addressing your problem statement." Remember -- the ONLY difference is in the sentence structure! (question: interrogative sentence; statement: declarative sentence)

- I've asked this "loaded question" in the past as to "what is research? what is its driving force?" And guess what answer I typically get: STATISTICS or DATA ANALYSIS!!!

- It's admittedly natural to give more weight to the "scariest" or "most complicated" part! BUT -- the statistics, as in all other parts of the research process, all centers around the RESEARCH QUESTION OR PROBLEM STATEMENT!!!!

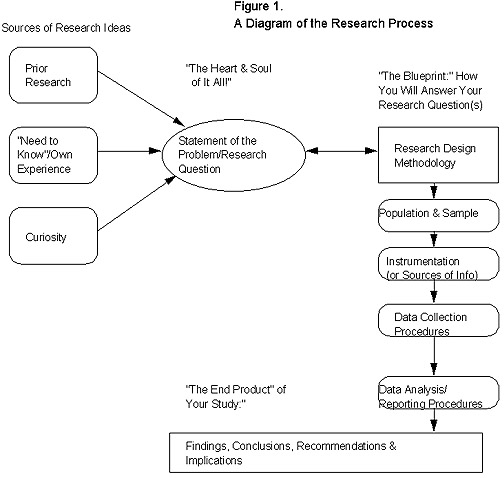

Diagram of the Research Process

These, then, would be the key steps in the research process:

- Identify your research question or problem statement.

This can come from:

- Something in prior research that piques your interest;

- A need to know based on practice (e.g., you observe a problem at work and wish to understand its causes better; and/or need to develop a solution to the problem)

- "Just because" curiosity about something!

- Specify the related research design ("blueprint" or "plan of attack" that you'll use to obtain the answer(s) to your research question(s)/problem statement.

We'll learn that these research designs come in "families," some of which "cleanly link" to given research questions or problem statements.

Open the link below for an overview from another instructor at Cornell University on Research Design.

Introduction to Research Design - Cornell University

Open this link and read about the major elements of a research design:

- Population and Sample: the WHO of your study (the population being "to whom do you wish to project or generalize your findings?" and the sample being "the subjects you actually observe, interview, send surveys to, etc., etc., or otherwise 'study' to get an answer to your question")

For practical purposes, we'll see later on that it might not be too feasible, time- and/or cost-wise to personally study EVERYONE to whom we wish to project or generalize! The task, then, will be to select or "draw" a smaller subset of subjects to actually "use" in our study. This is called a sample. We'll be learning various ways to draw a sample, as well as the relative tradeoffs of each different method.

Also -- please notice that I said "WHO" when it came to population and sample. These don't HAVE to be PERSONS (although they usually are: e.g., "all 4th-grade special education students enrolled in Arizona public schools for the 1993-94 academic year"); they CAN be THINGS (e.g., "all related special education curricula being used for/with these students"). In this case, we can say "WHAT" instead of "WHO." But since in the majority of "real-life" cases we are dealing with PERSONS instead of THINGS, I'll use "who" and "subjects" for population and sample references. And it'll be understood that these CAN be THINGS too!

- The "Instrumentation" or "Sources of Information" -- e.g., your "hands-on tools" for obtaining information needed for and about the population and sample in order to answer your research question(s)!

"Instrumentation" is any such tool involving "live and in-person" collection of information. Some examples are as follows:

- Mass-mailed rating scale surveys:

- Surveys with open-ended, fill-in-the-blank items;

- Questions about background and purchasing habits asked of subjects in a telephone interview;

- Open-ended questions about people's attitudes, feelings, likes and dislikes asked of 6-12 subjects in a relaxed setting for about one hour (this is called a "focus group interview");

- The same types of open-ended attitudinal questions asked of subjects one by one, either in person or by telephone (this is called an "individual interview");

- Your log book of notes of your observations taken of discipline methods used by a teacher in a primary grade classroom.

A Discussion of Survey Research

There are many other examples. Do you see how, in each of the above cases, it involves "live and in person" collection of data -- even if, as in the case of the mass-mailed surveys, you may never actually meet the subjects? But it's still a "live" person giving you the answers (hopefully, anyway ... !!!).

"Sources of Information," in contrast, involve getting your data from EXISTING sources -- e.g., what we call "archival information." The data already exist and you are locating, identifying and 'pulling from' these sources to fit YOUR research needs. Just a few examples of such sources of information are as follows:

- Pulling off the 4th grade ITBS scores in reading and math for the last 5 years from existing computerized databases in the school district office;

- Obtaining diaries written and kept by an individual who may be deceased but who is the focus of your area of interest -- and reading and selectively making notes and pulling quotations from these diaries;

- Obtaining policies on hiring and firing of school district classified staff from three preselected district offices -- and again, selectively 'reading and pulling' from these the information that you need to answer your particular research question(s).

Do you see how, in the above examples, the data/information/records, etc., ALREADY EXISTED (e.g., YOU weren't the 'original compiler') and may in fact have been created for totally different purposes at the time? But now you are needing to locate and use these sources to address your own particular, unique problem statement or needs to know.

Once you have completed this assignment, you should:

Go on to Group Assignment 1

or

Go back to It Starts with Question

Send Email to Walt Coker at Walter.Coker@nau.edu

Call Walt Coker at (623) 772-0305

Web site created by

the NAU OTLE Faculty Studio

Copyright 1998

Northern Arizona University

ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

|

It Starts with a Question.

It Starts with a Question.