|

Electronic Textbook:

"Ask and Ye Shall Receive:" An Introduction to Interviewing

"Ask and Ye Shall Receive:"

An Introduction to Interviewing

Last time out, friends, we talked about a popular channel of qualitative

data collection: participant observation. In the next series of lesson

packets, we'll zero in on perhaps one of the most widely used procedures:

interviewing.

This time around, we'll briefly take a look at some relative strengths

of interviewing, as compared with participant observation. We'll also

take a look at the dimensions along which interviewing itself may vary.

That is: as with Michael Quinn Patton's "five dimensions of participant

observation," you may be a bit surprised at the "leeway" you have with

regard to structuring interviewing. Finally, we'll end with Michael Quinn

Patton's excellent "matrix of interview question possibilities."

To get you feet wet, open the link below and read this overview of the

interview process in research.

Interviews

- Bill Trochim, Cornell

I. Relative Strengths of Interviewing

As we saw in the preceding topic, participant observation does have

a number of things going for it, in terms of being a desirable data

collection procedure. For one thing, an in-depth immersion

is possible. This in turn implies a larger number of sources of

information - many things being observed, all of which can serve

to "inform" the research question being addressed. The researcher's

perspective, in addition to those of others, can serve

as a cross-check on the 'reality' of that which is being observed.

On the other hand, as Michael Quinn Patton has pointed out, other key

sources of information "elude outside observation!" How are we to directly

"see" and "observe" important variables such as the following:

* Subjects' feelings, thoughts and intentions;

* Behaviors from an earlier point in time (i.e., have already

taken place) which influence those feelings, thoughts and intentions;

* Subjects' general thinking styles, frames of reference, how

they organize their worlds, and so forth

*** These CANNOT BE DIRECTLY

OBSERVED! The best way to gather information on them is to ASK!

*** As Michael Quinn Patton has stated, "The purpose of interviewing...is

to allow us to enter the other person's perspective."

Some may argue that "perceptions do not necessarily match reality."

True, but when you think about it, the same "threat to validity"

is also present to a degree in participant observation! Certainly

a situation can be 'rigged,' however subtly, when it is known

that there is an observer!(Ah, the bane of 'unannounced evaluation

observations' to every classroom teacher ..!) Whether conscious

or subconscious, subjects may present themselves differently to an outside

observer than they would "be" in "everyday life" in that setting. This

includes halo effects, Hawthorne effects, and reactive effects in general.

We would confront such potential incongruities or biases the same way

we do in the more general sense of validity and reliability cross-checks:

e.g., multiple observers, asking the same interview questions several

different ways, or better yet, building a multimethod design that incorporates

multiple qualitative data collection procedures (e.g., participant observation

balanced with interviewing) or quantitative and qualitative procedures

(e.g., adding in surveys, archival numerical data, etc.).

To remind our friends from Intro to Research and Research Design, it

is recognized that no single method of design and analysis is without

potential biases or flaws. Thus, the ideal in multimethod design and

analysis procedures is to "counterbalance" those biases, by using combinations

of two or more methods, to see if the results "converge" or point in

the same direction regarding the findings. This gives us a greater degree

of confidence that those findings are "valid," i.e., "we're picking

up something real," as opposed to a bias such as a please-the-researcher

halo effect!

II. Dimensions of Interviewing

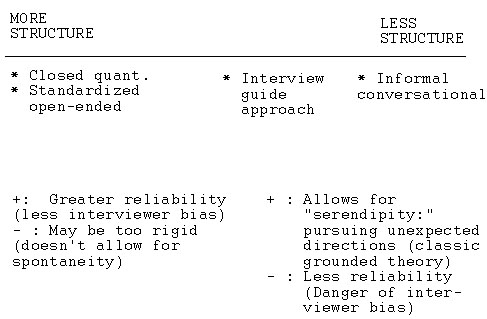

Michael Quinn Patton has also proposed the following excellent dimensions

of interviewing. My own 'take' on these is that in general, the tradeoff

is as follows. I've shown Patton's four major types of interviewing

as "starred elements" along the continuum. Below these, I show the "relative

pluses and minuses" of each extreme.

Figure 1.

The Basic Continuum of

Interviewing Procedures

In the preceding diagram, then, we can see that, of the

four methods identified by Patton, the major element of variation

is structure. Please note, too, that there are definitely

tradeoffs to be had at either extreme.

Such structure provides greater assurance that 'each interviewer

will ask the same questions in the same way(s).' Thus, the possibility

for interviewer bias, error, inexperience, etc., is reduced, which in

turn helps improve the reliability of the results.

Stop a minute and open the link below to get more familiar with the problem

of bias in the research interview.

Qualitative

Methods Workbook - Scroll down to Chapter 15

On the other hand, with greater predictability (in process, number

and types of questions, etc.) comes a concomitant loss of spontaneity.

We've learned that, particularly when it comes to very preliminary,

exploratory, grounded-theory work, such unanticipated (by the 'external'

interviewer) willingness to 'go with the flow' can lead to very fruitful

directions regarding "lived experience" as the subjects themselves perceive

them.

And the tradeoff is in exactly the opposite direction for the other

(right-hand side) extreme!

Too much spontaneity, particularly in the hands of relatively

unskilled, inexperienced interviewers, leaves open the risk of interviewer

error, subjects 'rambling, not covering areas which are "ex ante" important

to address in an (albeit open-ended) questioning fashion. Thus, the

reliability

of the study may suffer gravely in the event of a "too loose

and open" approach. This is particularly the case with less

exploratory, more 'confirmatory' types of investigations. Some of

the key variables,determinants, factors, outcomes, etc., are already

'known' to the researcher. This could be from prior work in the area.

Thus, it is important that those "known variables" be "covered" in as

objective and scientific a manner as possible. Their omission cannot

be left to chance, as it might in a too-spontaneous interview session.

Finally, before proceeding into Patton's excellent in-depth chart of

these interview possibilities, I do want to commend him for even including

that 4th one - on the left-hand side of the continuum above, called

"closed quant." This can cause confusion on the part of researcher

and subject alike!

Say you are an interview subject in such a situation. The researcher

is asking you a series of questions to which you are certainly replying

"in words." They may range from demographic; i.e., "What is your primary

ethnicity?" to seemingly even more open-ended ones: "What is the primary

reason that you chose to enter the teaching profession?"

Now, you may indeed be responding qualitatively - giving

verbal responses. For the second example, above, in fact, you

may choose to give a lengthy verbal explanation of your primary motivation

in choosing teaching as your profession - complete with richness and

depth of feelings and emotions!

However, if the interviewer is recording your answers by checking

off a choice on his/her corresponding interview form - such as a

category for "Ethnicity" or even a category that in the interviewer's

expert opinion "most closely matches" the lengthy verbal answer you've

just given for "teaching motivation" - then this so-called "interview"

is really a quantitative data collection procedure! For

it is possible that all the 'words' will be tallied up and quantified

only: e.g., "Total number and percent of respondents who are Navajo;"

"Total number and percent of respondents who chose teaching due to 'wanting

to make a difference in students' lives (if this was a choice on the

interviewer's response sheet as he/she listened to and classified your

answer)," etc.

That, then, is the nature of the "closed" in the label, "closed

quantitative interview." Regardless of how you choose to verbalize

your responses, they will all eventually be forced into such predetermined,

'closed' categories and tallied up for the reporting and analysis.

This is what makes this "interview" in actuality a quantitative,

not qualitative, procedure!

Now -- let's revisit those four types (3 qualitative, 1 quantitative)

of interviewing in Michael Quinn Patton's own words! How about it?

Table 1.

Variations in Interviewing Procedures

adapted from: Michael Quinn Patton,

How to Use Qualitative Methods in Evaluation

(1987: Sage Publications, Inc.)

| Type of Interview |

Characteristics |

Relative Strengths |

Relative Weaknesses |

|

Informal conversational interview

|

Questions emerge from

the immediate context & are asked in the natural order of things;

there is no predetermination of question topics or wording. |

Increases salience & relevance

of questions; interviews are built on & emerge from observations;

the interview can be matched to individuals & circumstances. |

Different information

collected from different subjects with different questions.Less

systematic & comprehensive if certain questions do not arise "naturally."

Data organization & analysis can be quite difficult. |

| Interview guide approach |

Topics & issues to be covered

are specified in advance, in outline form; interviewer decides

sequence & wording of questions in the course of the interview. |

Outline increases comprehensiveness

of data & makes data collection somewhat sys-tematic for each

respondent. Logical gaps in data can be anticipated & closed.

Interviews remain fairly conversational & situational. |

Important & salient topics

may still be inadvertently omitted by the interviewer. Interviewer's

flexibility in sequencing & wording questions can result in sub-

stantially different responses, thus reducing the comparability

of those responses across different subjects. |

| Standardized open-ended

interview |

The exact wording & sequence

of questions are determined in advance. All interviewees are asked

the same questions in the same order. |

Respondents answer the

same questions thus increasing compara- bility of responses; data

are complete for each person on the topics ad-dressed in the interview.

Reduces interviewer effects & bias in the case of multiple interviewers.

Permits decision makers to see & review the "instru- mentation"

(i.e., the set of common questions) in advance of the interviews.

Standard format also facilitates subsequent organization & analysis

of the interview data. |

Little flexibility in adjusting

the interview to individuals & unique circumstances; standardized

wording of questions may inhibit, constrain & limit the "naturalness"

of interview questions & answers (i.e., interaction between interviewer

& subject). |

| Closed quantitative interview |

Questions & response categories

are determined in advance. Res- ponses are fixed; they are 'slotted'

into these predetermined fixed categories for compilation & analysis. |

Data compilation & analysis

is relatively straight-forward; responses can be readily aggregated

& also easily compared across individuals & sub- groups; many

questions can be asked in a relatively shorter time with the fixed

format. |

Respondents' verbalized

perceptions, actual experiences, feelings, etc. must be made to

'fit' into those predetermined categories; may be perceived as

im- personal, irrelevant, & somewhat mechanistic. Can distort

what respondents "really mean" or have actually experienced by

having the limited, fixed response choices. |

As you scan the preceding comparative rows of the matrix

of possibilities, you've probably already realized that it is possible

to have a single interview session which is a "hybrid,"

or a mixture of the different methods, for different parts of

the interview.

The structure can vary in either direction. For instance,

the interviewer may choose to start the session with 'neutral, structured,

warm-up' demographic questions. These responses may be recorded as closed

quantitative items. Then, as the interview progresses, the interviewer

may "loosen up" with gradually more open-ended questions, and perhaps

close by totally following the direction of the subject's responses

-- e.g., spontaneous follow-up prompts as opposed to prepared questions

at that point.

The opposite direction is also possible. The interviewer

may opt to "set a blank stage" in the beginning, then gradually focus

the questions, and finally bring closure to the session with a standardized

set of (quantifiable, closed-ended) demographic or other types of questions.

As can be seen from the preceding Part III discussion,

the "happy medium" might be captured by the following two procedures:

1. Standardized open-ended interview; and

2. Interview guide approach.

There is an excellent source on standardized open-ended

interviewing that I'd like to recommend to you. It is by Floyd J. Fowler,

Jr. (a noted survey design expert, by the way, who's based at the University

of Massachusetts, Boston) and Thomas W. Mangione. It is entitled Standardized

Survey Interviewing: Minimizing Interviewer-Related Error and was

published in 1990 by Sage Publications, Inc. in Newbury Park, California.

We'll be spending more time in future modules on the second

alternative, the interview guide approach. As we have seen in

Table 1, above, this one attempts to balance the open-ended,

'go with the flow' if warranted nature of qualitative research with

some preplanned directions (e.g., basic question topics) to enhance

reliability and comparability. For now, I'd like to mention that

other terms for "interview guide" that are popularly used include

"questioning route" and "interview protocol." We'll be

using these interchangeably.

Now -- as we head into this area, let's close out our

introduction to interviewing by taking a look at Michael Quinn Patton's

excellent "matrix of question options." This will get you started

thinking about the basic categories or types of questions that

you might ask in an interview. These will comprise the rows of

this matrix. The columns, on the other hand, represent the time

dimensions within which you can plan and structure your questions.

Not all questions need be about the present - nor should they

necessarily be! Remember, qualitative is about 'rich, thick description!'

Not seemingly precise Type I error rates, p-values, etc.! Thus, we might

need for subjects to "guess-timate" about the future - and likewise

benefit from their "best recall" of the past!

IV. Matrix of Interview Questions

Let's begin by sketching out this matrix and then also

briefly discuss each of the types (rows). This matrix appears on the

following page. Many researchers have found it helpful to "fill in"

such a matrix when they are initially drafting and revising their tentative

interview questions.

Table 2.

Matrix of Question Options

adapted from: Michael Quinn Patton,

How to Use Qualitative Methods in Evaluation

(1987: Sage Publications, Inc.)

| Category/Type of Question (Rows)/ Time Dimension for

Framing the Question (Columns) |

Past |

Present |

Future |

Behavior/

experience

questions |

Fill in your actual planned questions |

Fill in your actual planned questions |

Fill in your actual planned questions |

Opinion/

value

questions |

Fill in your actual planned questions |

Fill in your actual planned questions |

Fill in your actual planned questions |

Feeling

questions |

Fill in your actual planned questions |

Fill in your actual planned questions |

Fill in your actual planned questions |

Knowledge

questions |

Fill in your actual planned questions |

Fill in your actual planned questions |

Fill in your actual planned questions |

Sensory

questions |

Fill in your actual planned questions |

Fill in your actual planned questions |

Fill in your actual planned questions |

Demographic/

background questions |

Fill in your actual planned questions |

Fill in your actual planned questions |

Fill in your actual planned questions |

Now, let's step through the different types/categories

(rows) to give you a feel for what sorts of questions you might be filling

in for each of these!

Experience/

Behavior Questions: |

These deal with subjects' actions - be they

past, present or future. Through such questions, you'd be getting

the subjects to describe activities, decisions, behaviors, etc.,

that would actually be observable. In evaluation research, for

example, these might relate to a program. "If I followed you through

a typical day [of Program/Activity X], what would I have seen you

doing?" These types of questions, by the way, are sometimes called

"simulation" questions. The idea is to simulate the types,

nature, sequence, etc. of actual behaviors or activities. |

Opinion/

Belief Questions |

These questions are aimed at understanding subjects'

'world-views' of things, as alluded to on pg. 1 of this lesson

packet. How do they cognitively structure their reality?

Anytime you see "keywords" such as the following, you can be sure

you have an opinion/belief question: "What is your opinion

of [...]?" "What do you think about [...]?" "What do you

believe about [...]?" As a cautionary note, these are sometimes

confused with the next two categories: feeling and knowledge

questions. |

| Feeling Questions: |

Unlike beliefs, which deal with "cognitive

subjectivity," feeling questions deal with "affective

subjectivity." Here you are tapping into subjects' emotional

responses - i.e., feelings of happiness, fear, anxiety, confidence,

and the like. |

Knowledge

Questions: |

While feelings and beliefs are subjective,

knowledge questions deal with subjects' factual information.

What things does the respondent know about [...]? Patton

illustrates this for an evaluation example. Knowledge of a social

program may consist of: what services are available, who is eligible,

how long people spend in the program, rules and regulations, enrollment

procedures, and the like. |

Sensory

Questions: |

These are just what they sound like! They deal with

what is heard, touched, seen, tasted, or smelled. Example:

"When you walk through the doors of your mother's house, what do

you see?" "What do you hear the counselor saying to you at the beginning

of each session?" |

Background/

Demographic

Questions: |

These are the standard items that describe subjects'

identifying characteristics. They may include age, educational

level, annual income, time enrolled in the current program, and

place of residence. At first glance, they may appear to also

be knowledge (factual) questions. In a sense, this is true: but

they relate to a particular subtype of "facts:" those pertaining

directly to the subject. Patton characterizes them as "more routine

in nature" as a result. |

The time dimension (columns of Patton's Table 2, above)

may seem comparatively self-explanatory. For instance, for a behavior

question, the interviewer may ask the subject: what he/she did yesterday;

is doing today; or plans to be doing tomorrow.

However, I would like to introduce to you a special label

for "past" questions, because it is so popularly used in focus group

interviewing, in particular (the topic of our next lesson packet). This

is called the "think back" question. By asking the subject

to "think back" to some past experience or event, the interviewer

is mentally taking the subject back into that past reality. He/she could

presumably 'flesh out the details' of that past by asking virtually

any type of question in that context.

"Think back to your first day as a participant in [Program

X.] What did you do on that first morning?" (Experience/Behavior Question)

"... and what did you think of the announced objectives

of the program?" (Opinion/Value Question)

"... and what were your feelings as you were asked to

reflect upon the conclusion of the warmup activity?" (Feeling Question)

" ... and what was the first thing the group facilitator

said to you?" (Sensory Question)

"...and what were the stated objectives of that program

as announced by the keynote speaker?" (Knowledge Question)

"...and how long had you been employed as an educator

in that school district at the time that you enrolled in [Program X]?"

(Background/Demographic Question)

Not all of these categories of questions, nor the time

period (past, present, or future), in Patton's grid, would necessarily

apply equally, or even be relevant, to a particular interview context.

Rather, this grid is meant as an "imagination/possibility-stretching

guide," to get you to thinking about as many different types of potentially

useful interview questions as possible.

Next time, we'll take an in-depth look at a particularly

popular and "information-rich" type of interview setting: the focus

group.

Till then, please remember - it's OK to have a little

fun with the process ... !

Once you have finished you should:

Go back to Introduction

to Interviewing

E-mail M. Dereshiwsky at statcatmd@aol.com

Call M. Dereshiwsky at (520) 523-1892

Copyright © 1999 Northern Arizona

University

ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

|