|

BME637

: The Class

: Communication

: Theory

: Online Lesson 1

Online Lesson 1:

Part III: An Illustration

Small Group Reading Lessons

Let's explore small group reading lessons. In a teacher-centered reading

lesson, students are sitting in a square or circle (depending on the table

shape). They are expected to display the expected postural configuration

for reading. That is, they have to sit straight, with both hands on the

tabletop. The teacher monitors the students in the group making sure that

everyone is sitting correctly and making sure that their books are opened

to the right page. The teacher makes explicit the task at hand. S/he tells

the students that each will read one paragraph taking turns starting from

the right side and moving through the circle in order. So Johnny, sitting

next to the teacher, reads first, followed by Maria who is next to him,

followed by Jack who is next to Maria. The turns at reading continue until

the last student reads his/her paragraph. This is a typical teacher-centered

reading lesson. It is teacher-centered because the teacher controls the

turns at reading and more importantly, the teacher is the only participant

allowed to interact or correct individual students as they read. The other

students must display the expected "engagement" etiquette as

each individual student reads. What are teacher assumptions in this lesson?

The teacher assumes that the students are engaged because they are displaying

the expected engagement etiquette that the teacher reinforces. They are

expected to read the same paragraph that the reader is reading, and they

display this by looking at the book, being on the right page, pointing

with their fingers the paragraph at hand, and sitting "quietly"

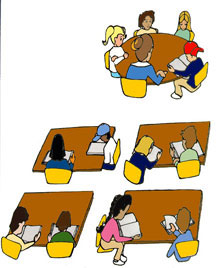

until it is their turn. In Illustration A below I provide a picture of

what students may be doing in this teacher-centered lesson.

Illustration A Illustration A

When Johnny

began to read, what would a smart child like Maria really do when she

knows she has to read the next paragraph after Johnny finishes his? She

probably is practicing reading her own paragraph. What may the other students

be doing when it isn't their turn? They too could be practicing at their

own paragraph as Johnny reads. How does the teacher detect that all the

students are engaged in the lesson as individuals take a turn at reading?

It is now Maria's turn at reading and what might Johnny be doing? While

he's displaying the appropriate etiquette for group reading he also might

be disengaged because after all, he's already finished his assigned task.

How does the teacher know that he is still engaged? He could be faking

engagement, and all the teacher has as evidence of engagement is the proper

physical display of reading etiquette. Why should a student read along

silently with others when they are no longer readers? Why would they read

silently when they are no longer held accountable since the teacher switches

focus from one reader to the next? There is no guarantee that students

in these kinds of teacher-centered contexts are actually engaged! Students

and people like you and me are socially bright and know when to enter

and leave contexts, i.e., they know how to engage and disengage without

being detected.

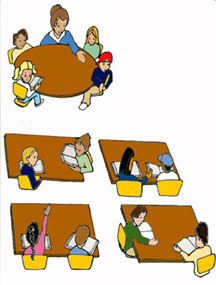

Illustration B is an example of a student-centered small group reading

lesson. For my doctoral dissertation, "Collective Engagement in the

Segundo Hogar: A Microethnography of a bilingual classroom" (1986),

I described a student-centered small group reading lesson where the students

shared the responsibility of teaching. The teacher did not have a linear

approach to turn taking. She asked for volunteers. No one knew his/her

turn in advance. Moreover, she did not specify the limitation of one paragraph

per reader. Whenever Juanito read and had trouble in reading, each of

his peers would help, often helping simultaneously as in Illustration

B.

Illustration B

The teacher would be the last person to help the reader and usually

the teacher would only intervene when the student peer teachers were not

providing the appropriate help. So when the teacher detected that all

the students were having problems with the same issue, then she provided

correction to not only the reader but to all the group who were on-task,

and truly engaged in the reading lesson as evidenced by their helping

interactions! How could they help their peers if they weren't paying attention

to the reading? My research showed that these children in a student-centered

reading lesson were actually engaged as evidenced by they contributions

to the activity. There were times in the reading lessons I studied that

the teacher disengaged herself from the lessons due to a monitor coming

in to deliver a message from the principal's office or misbehavior by

the other students not in the lesson. In teacher-centered lessons, students

also disengage themselves when the teacher disengages because the lesson

is dependent on the teacher. They normally stop everything and re-engage

only when the teacher returns to the lessons. In our example of the student-centered

lessons, when the teacher disengaged herself from the lesson, the lesson

did not stop; it continued without the teacher because teaching was a

shared responsibility ----the students remaining engaged in the lesson!

Let's move on to another example that Dr. Ray McDermott and his associates

discovered in their research. I also observed similar phenomena in my

own classroom research. This has to do with time on task and lesson engagement.

In the 80's there was lots of research that found that the more time you

spend on an academic task, the more you learn that academic content! This

seems very logical and I wonder why millions of dollars were spent to

come up with this finding. Related to this finding was that if time on

task is important, how does one know that they are actually on task, that

is, actually engaged in the academic activity? In this regard, McDermott

compared the reading activities of high and low reading groups in a classroom.

He focused on time on task and lesson engagement as he compared these

reading groups. Study Illustration C below.

Illustration C

This is a top view layout

of a classroom with the teacher teaching the "high" group (meaning

the best readers in the class). The teacher allocates 20 minutes of reading

time for each group. The approach for each reading group was teacher-centered

as the example above. The high reading group lesson went smoothly and

the teacher was totally engaged in the lesson for the 20 minutes allotted.

They read and discussed the passages and they seemed to be engaged in

the lesson. Let us assume that even in this teacher-centered lesson, everyone

was engaged in the reading activity. They had 20 minutes of quality reading

time. In the low reading group (the worst readers---and in McDermott's

research, the worst readers were minority children), it was a different

story altogether. See Illustration D.

Illustration D In this top view of the same classroom

we see differences in teacher position at the reading table as compared

to the high group. It was found that in the low reading group there were

many outside interruptions, and the teacher and students were consistently

disengaged. In the high group there were no interruptions. Can you see

why? It was discovered that the low group did not spend the full 20 minutes

engaged in the lesson due to the many outside interruptions that the teacher

allowed and acknowledged. Comparing the time spent engaged in the high

and low groups, the high spent more time on task while the low group spent

less time on task, and this contributed to the widening gap between the

two groups. The good readers became better readers while the slow readers

fell farther behind. What happened in this low group scenario? The teacher

working with the high group (Illustration C) had her back to the rest

of the class concentrating only on her fast readers! The rest of the class

did not have eye contact with the teacher so they couldn't get her attention.

When the teacher worked with the low group, she placed herself facing

not only her reading group but also all the class! Students, like all

of us, know how to get people's attention. It is easier to get the teacher's

attention when one is in line with the teachers view or periphery! One

can make large arms movements to get the teacher's attention and if one

can connect with the teacher's eye gaze, then one can initiate an interaction

forcing the teacher (and the reading students) to disengage from the lesson.

This is what happened, and this low group of readers spent much of their

allotted 20 minutes disengaging and re-engaging taking precious time from

quality reading lessons…and this was simply due to the position at the

reading table. The reasons for these two different teacher positions may

very well be that the teacher enjoyed teaching reading with "good"

readers. Don't we all? It is a harder task to teach slow readers and many

teachers do not enjoy teaching children pronunciation and others problematic

issues. It is also hard to have cognitively demanding higher-order discussions

on reading comprehension due to poor reading skills. I can see why some

teachers may want to minimize this "pain." But this is not what

I call good teaching practices. Nevertheless, the point of this example

is that a simple change in teacher position can have major educational

implications!

We can expand the "time on task" theory as we observe other

areas in classroom culture. For example, "getting ready" to

end a lesson and "getting ready" to begin a lesson takes time---that

is takes valuable time away from academic activities. How long does it

take to begin a lesson? I have observed many teachers spending more than

five minutes just to get students engaged in the lessons, and when the

lesson is over, another five minutes are spent in disengaging from that

lesson (putting your seat back, putting your books and materials away,

etc.). Then another five minutes are spend to start a new academic activity!

If one were to sum the number of minutes spent in a normal classroom day

for "getting ready and getting done," one would be astounded.

Once you have finished you should:

Go on to Online Lesson - Part IV

or

Go back to Topic 1: General Communication Theory

|