![]()

Masterpieces of Western Literature

| Unit 6 |

|

English 201:

Masterpieces of Western Literature |

| .Unit 6 Reading | Course Reading | Entry Page |

| Introduction | Background | .Explication | Questions | Review |

Endurance: The first theme illustrated in this section is obvious. Life is troublesome. We must struggle to endure. Possibly in that struggle we may accomplish deeds that both define our identity & of which we are proud. Dangers include not only violence (Sklla, Kharybdis), but timidity, laziness, or addiction evident with the Lotos Eaters & the Seirenes.

Civility: Polyphemos the Kyklops illustrates brute power without civility. It is blind, enraged, & paradoxically, impotent. Aristotle & Plato both thought that virtue could only be found in city life. Living as a hermit may have been an acceptable way of life for Christians, but the illustration of such a life in Homer is offered by Polyphemos.

The

Culture of the Body: In

his Nicomachean Ethics, Aristotle wrote:

He who exercises his reason

& cultivates it seems to be both in the best state of mind & most

dear to the gods. For if the gods have any care for human affairs,

as they are thought to have, it would be reasonable both that they should

delight in that which was best & most akin to them (i.e. reason) &

that they should reward those who love & honour this most, as caring

for

the things that are dear to them & acting both rightly & nobly.

You may think that the gods have bodies,

but it might be more accurate to say that they take various forms.

Athena appears as Mentor & the "awesome one in pigtails," as well as

in her usual form. Above all the gods don't have bodies that get

sick, old, & ultimately perish. In Homer's world of 700 bce,

the life of the philosopher, being dedicated to the culture of the mind,

is not yet possible. It will become possible only with the invention

of the Greek city. Nonetheless, Homer illustrates the futility of

dedicating one's life exclusively to the culture of the body (in athletics

& the military). The bodies of AK, Aias, & AG are glorious,

but short lived. If anything survives death, it is certainly not

the body. It may be the mind. In his work, On the Soul,

Aristotle says:

The case

of mind is different; it seems to be an independent substance implanted

within the soul & to be incapable of being destroyed.

Aristotle differentiates the mind from

the soul, because:

Thinking, loving, & hating are affections

not of mind, but of that which has mind . . . That is why, when this

vehicle decays, memory & love cease; they were activities not of mind,

but of the composite which has perished; mind is, no doubt, something more

divine & impassible.

Aristotle's good news is that the mind is eternal. The bad news is that everything that makes us unique individuals, our idiosyncratic memories & associations, fade. In any case, both Plato & Aristotle consider the polis to be the necessary institution to deliver or make possible the good life, the fully human life that ultimately prepares one to be fit company for the gods in the next world. Contrast that possibility with the "dimwitted dead . . . camped forever [in the dark], the after images of used-up men." Above all else these shades find the loss of the body means the loss of everything that made life significant.

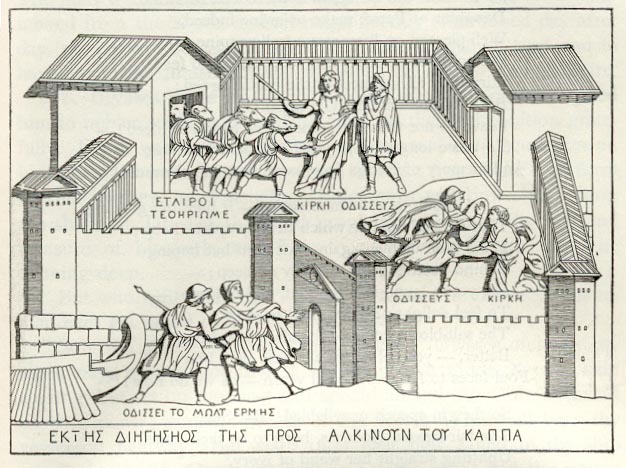

Kirke's House (notice the hog's heads on the men at the top)

Click on the next section: Background

above.