Unit 6

English 203:

Literature of the NonWestern World

|

Unit 6 |

English 203: Literature of the NonWestern World |

| Introduction | .Explication | Questions | Review |

Explication:

Reading: 746-811

Sakuntala

1411-29 Bhakti Poets

| Bhakti Poets |

Sakuntala:

The closest parallel in the West to Kalidasa's play is a light opera. Unlike ancient Greek tragedies, there is very little plot development in Sakuntala. Perhaps we should expect that, because Hinduism considers actions in this world to be ephemeral & consequently unimportant in themselves. Your text says that "individual will & personal destiny . . . have no place in this [Hindu] vision" (747). The word for Sakuntala is "charming." It offers theatrical elegance & spectacle: "extensive use was made of stylized gesture, facial expression, eye movement, music, & dance in enacting the poetic text" (746). In so far as there is a theme, it is, of course Hindu. The theme illustrates emotional detachment, restraint, & discipline: "At first each [character] acts impulsively, moved by passion. In the end, each is refined by duty [Dharma] & chastened by suffering" (747).

Act 1:

The play begins,

appropriately enough with a poetic suggestion of the Vedic sacrifice, which

mimics the original sacrifice that created the universe. It ends

by invoking the blessing of Shiva:

1.1 The

water that was first created,

the sacrifice-bearing fire, the priest,

the time-setting sun & moon,

audible space that fill the universe . . .

. . . may Lord Siva come to bless you

The innocently romantic

mood & scene are set by the first short song:

1.28

Sensuous women

in summer love

weave

flower earrings

from fragile petals

of mimosa

while wild bees

kiss them gently.

Ashrams or religious

sites in the forest are safe havens for all creatures. Even the king

is told that he can't hunt there: 1.78. You see the caste hierarchy

illustrated when a Brahmin monk scolds the Khastriya caste king:

1.85

Your weapon should rescue victims, not destroy the innocent!

Everyone is saccharine

polite. Instead of resenting the monk's tone, the king says:

95

I welcome your blessing.

Everyone appreciates

everyone else's dedication. Thus the monk tells the king:

1.99

When you see the peaceful rites of devoted ascetics,

you will know how well your scarred arm protects us.

The king quickly

indicates that he is not as emotionally restrained as he first appeared.

It is one thing to be respectful to an old monk; Sakuntala is something

else again. Why does the king think:

K1.154

The sage . . . show[s] poor judgment in imposing the rules of the hermitage

on her.

The king's romantic

interest in Sakuntala is obvious in his recognition that:

1.182

impatient youth is poised

to blossom in her limbs.

The king's decision

to follow his emotions rather than Dharma is, obviously, a mistake:

1.201

when good men face doubt,

inner feelings are truth's only measure.

Falling in love at

the first sight of Sakuntala, the king is even jealous of the bees that:

1.208

hover softly near

to whisper secrets in her ear:

a hand brushes you away,

but you drink her lips' treasure--

while the truth we seek defeats us,

you are truly blessed.

In medieval Western

Romance, Lancelot or some other knight hoped that he could save beauty

from the beast. Dragons represented something very formidable, if

not evil. See how operatic Sakuntala is? The king is delighted

to be able to save Sakuntala from a bee:

1.214

This dreadful bee won't stop. . . . Save me! Please save me!

This mad bee is chasing me!

Notice the stage

direction. Her friends are laughing, knowing that there is no real

danger. They suggest:

1.217

How can we save you? Call King Dusyanta. The grove is under

his protection.

Ironically, the king

does step forward to save Sakuntala, concocting a cover story about being

1.252

appointed by the Puru king as the officer in charge of religious matters.

I have come to this sacred

forest to assure that your holy rites proceed unhindered.

Interestingly, Sakuntala

is also falling in love at the first sight of the king. She innocently

asks herself:

1.238

When I see him, why do I feel an emotion that the forest [hermitage] seems

to forbid?

The king was concerned

that he could not approach Sakuntala because she was a Brahmin & he

was a Khastriya. The king's ardor is fueled by the discovery that

she is of his caste:

1.270

Kanva [the Brahmin priest that the king assumed was Sakuntala's father]

is her father because he

cared for her when she was abandoned.

Notice again what

it is that Hindu champions conquer. They are not champions because

they can conquer some other warrior. They are champions because they

(& not us) can conquer their emotions:

1.273

Once when this great sage [Sakuntala's father] was practicing terrible

austerities . . . he became so

powerful that the jealous gods sent a nymph . . . to break his self-control.

No doubt the king

is pleased to learn that her monk father:

1.297

does intend to give her to a suitable husband.

For who could be

more suitable than the king?

Notice the dalliance in the play. Dalliance is playful flirtation. It is gently teasing, elegant, & obviously has romance as an object. But it is important not to bluntly seize the object or even to attain the object too soon, because the delicious anticipation of dalliance, paradoxically, will be lost in attaining the beloved object. Of course this is as true in the West as in Asia. Hinduism, however, adds another layer by suggesting that we never fully attain or possess any object, not even our own historic identity. Far from being a tragedy, this recognition should shift our attention to dalliance. Every moment of life should be dalliance or Ramalila (the divine play of God). Everyday we should wake with the feeling of having just fallen in love with beauty. Like Sakuntala, our days should be filled with flowers & honey, with music & incense, & above all with love. The king wonders:

1.335

Can she fell toward me what I feel toward her?

She won't respond directly to my words,

but she listens when I speak;

she won't turn to look at me,

but her eyes can't rest anywhere else.

Before the king can

press matters to some more explicit state, his retinue causes a ruckus

searching for the lost monarch:

1.355

My palace men are searching for me & wrecking [the peacefulness of]

the grove. I'll have to go back [to duty/Dharma].

But he does not

go back to duty as Act 1 ends, confessing that:

1.365

I can't control my feelings for Sakuntala.

Act 2:

Act 2 opens with

the buffoon complaining about the lovesick king who is hunting birds or

the girl who was raised by birds (which is what Sakuntala's name means).

The king is still unsure of Sakuntala's feelings, reflecting that:

2.23

A suitor who measures his beloved's state of mind by his own desire is

a fool.

Even the buffoon

reminds the king of his duty (Dharma):

2.44

You neglect the business of being a king

Of course the king

has his beloved in mind, when he says:

2.100

Ascetics devoted to peace

possess a fiery hidden power

Literally he would

be talking about Shakti (cf. Chinese/Japanese chi) or a mystic

power generated by tapas (austerities or resisting inclination &

desire). Ironically we can read those same lines & understand

that if the ascetic is Sakuntala, she possesses a "fiery hidden power"

that burns in the king -- the power of kama or love. The king

continues to argue (in large part in order to convince himself) that his

real duty or higher duty lies with the Brahmin ascetics rather than in

his caste duty as a Khastriya warrior & monarch:

2.173

Tribute that kings collect

from members of society decays,

but the share of austerity

that ascetics give lasts forever.

Notice footnote 8 on p. 765: "While Dusyanta may appear worldly to a modern audience, his sacred royal office [Khastriya Dharma], his respect for the sages, & his disciplined adherence to the standards of dharma make him, in the sages' eyes, a person of tremendous self-control." It is true that the king correctly understands that his duty [Dharma] is to provide a haven for those above him, viz., the Brahmin priests whose lives make the entire kingdom holy. Nonetheless, he is in love with the pretty little thing who lives in the heritage.

Act 3:

The stage direction

says “the king enters, suffering from love.” He clearly recognizes

his dilemma:

3.14 I know the power

ascetics have

& the rules that bind her,

But I cannot abandon my heart

now that she has taken it.

Sakuntala also confesses

her love for the king:

3.86 Since my eyes

first saw the guardian of the hermits’ retreat, I’ve felt such strong desire

for him!

She sings about her

love & is overheard by the king:

3.148 I don’t know

Your heart,

But day & night

For wanting you,

Love violently

Tortures my limbs,

Sakuntala’s friends

encourage the romance, telling the king:

3.175 Since she

first saw you, our dear friend has been reduced to this sad condition.

You must protect her & save her life.

Save her life!

Duty & desire suddenly seem to merge. Still Sakuntala has scruples:

3.203 I cannot sin

against those I respect!

The king tells her

that their love is a special case:

3.212 Don’t fear your

elders! The father of your family knows the law [Dharma].

When he finds out, he will not blame you.

The daughters of royal sages often marry

in secret & then their fathers bless them.

The usual process in a situation like this is to approach one’s parents & have them make the arrangements for marriage.

Act 4:

The lovers are too

impetuous or too deeply in love to respect Asrama-Dharma.

The marriage occurs between acts 3 & 4. Act 4 opens with Sakuntala’s

friend telling us:

4.2 I’m delighted that

Sakuntala chose a suitable husband for herself, but I still feel anxious.

She says she is anxious

because the king “returned to his palace women in the city” & may quickly

forget the conquest he has made, abandoning Sakuntala. She is also

anxious about:

4.7 what Father Kanva

will think when he hears about what happened.

If Sakuntala’s

surrogate father, Kanva, condemns her, it is hard to imagine a reconciliation.

If Kanva says she has violated Dharma, what can he do? He

cannot himself renounce the obligation of Dharma because of his

emotional attachment to his daughter. The play would have to develop

into a tragedy. To avoid this Kalidasa develops a somewhat clumsy

parallel from lines 17 on. Sakuntala fails to greet a guest, who

never appears on stage. This guest is evidently a powerful tantric

sage who is also very testy, because he curses Sakuntala:

4.22

So . . . you slight a guest . . .

Since you blindly ignore

a great sage like me,

the lover you worship

with mindless devotion

will not remember you

Sakuntala is:

4.57 thinking about

her husband’s leaving, with no thought for herself, much less for a guest.

The “sage,” Durvasas, does the work of Kanva, condemning Sakuntala for giving into her emotions but allowing for Sakuntala to suffer through the consequences of her impetuousness & ultimately be reconciled to both her father & husband.

Months pass with

no word from the king. Kanva still doesn’t know:

4.85

that Sakuntala is married to Dusyanta & is pregnant.

The problem is serious. What should we do?

In the next few lines

Kanva discovers Sakuntala’s condition & says he will send her to her

husband, apparently thinking that she was reluctant to leave him (4.95).

Kanva conducts a marriage ceremony (4.165) even though the bridegroom is

not present. His approval is explicit:

4.212 Your merits

won you the husband

I always hoped you would have

Your text has a footnote

explicating the scene when Sakuntala leaves her father for her husband.

She says:

4.284 How can I go

on living in a strange place [i.e., the husband’s extended family home],

torn from my father’s side.

Indian brides were

usually teenagers. They would no doubt be attracted by a marriage

that was a rite of passage, making them adults. They would also,

no doubt, be interested in the sexual opportunity. On the other hand,

they would have to leave a family where they were loved & doted on

to enter their husband’s extended family. He is no doubt interested

in his bride, but he is also his mother’s son & mom has some very equivocal

feelings. Often some part of her feelings harbor resentment against

the interloper who threatens to take her son away from her. The new

bride knows nothing about the workings of the new family & is often

teased or treated badly by the bridegroom’s siblings, especially his sisters,

as well as by his aunts – all of whom live in the same house. It

is unlikely that the husband will quickly shift his commitment away from

mom to his new bride. In fact he has almost always married the girl

that mom picked for him. Consider the advice that Kanva gives his

daughter:

4.288 When you

are . . .

absorbed in royal duties & in your son

. . . the sorrow of separation will fade.

Kanva’s advice (which

is also the advice of Indian culture) is to have a son & emotionally

invest in that relationship more than in any other relationship.

Sakuntala’s friends

remind her to show the king the marriage ring that he has given her:

4.295 If the king seems

slow to recognize you, show him the ring engraved with his name!

Act 5:

You know enough about

literary plots to recognize such foreshadowing. We naturally suspect

that the ring will be lost or stolen. We can also recognize that

Sakuntala must be reluctant to use the ring, feeling that if she has to

do so, it means that the king no longer loves her. We are suppose

to recognize that the king has also suffered:

5.63

Every other creature is happy when the object of his desire is won,

but for kings success contains a core of suffering.

. . . a kingdom is more trouble than it’s worth,

5.71

You sacrifice your pleasures every day

to labor for your subjects

When Sakuntala comes

to the palace, the king is struck by Sakuntala, as though he is falling

love all over again:

5.114 Who is

she? Carefully veiled

to barely reveal her body’s beauty,

surrounded by the ascetics

like a bud among withered leaves.

The king is surprised

when he is told that Sakuntala is his wife, asking:

5.165 Did I ever

marry you?

5.183 I don’t

remember marrying this lady. How can I accept a woman who is visibly

pregnant when I doubt that I am the cause?

The group from the

hermitage, including Sakuntala, believe that the king is simply choosing

to forget his duty to his wife. Sakuntala tells him that he “deceived

her in the hermitage” (5.201). When she attempts to show him his

ring, she discovers that she has lost it (5.212). The king admonishes

Sakuntala for attempting to deceive him:

5.227 Thus do women

further their own ends by attracting eager men with the honey of false

words.

Isn’t it strange

that Sakuntala’s friends now reject her, apparently believing the king’s

version of events?

5.278 If you

are what the king says you are,

you don’t belong in Father Kanva’s family

Act 5 ends with Sakuntala

abandoned by both her husband & her father (once again, Kanva is indirectly

involved, since it is the entourage from his heritage who abandon Sakuntala).

Even in this darkest moment, we suspect that the king will soon come to

his senses:

5.321 I cannot remember

marrying

the sage’s abandoned daughter,

but the pain my heart feels

makes me suspect that I did.

Act 6:

The ring is found

& the king remembers:

6.122 When he saw the

ring, the king remembered that he had married Sakuntala in secret &

had

rejected her in his delusion. Since then the king has been tortured

by remorse.

The king is so distraught

that he feels unqualified to do his varna-dharma:

6.441 When I

don’t even recognize

the blunders I commit every day,

how can I keep track

of where my subjects stray?

Act 7:

We have the reverse

of the situation in act 3 when the king was told that he must save Sakuntala’s

life by responding to her love (3.176). Now it is Sakuntala’s turn

to save not only the king, but the kingdom. The king is evidently

thinking of abdicating to pursue an ascetic life:

7.184 As world

protectors they first choose

palaces filled with sensuous pleasures,

but later, their homes are under trees

& one wife shares the ascetic vows.

The king is evidently

considering a kind of reversal: he will follow Sakuntala & adopt her

lifestyle. Musing on this, the king just happens to meet Sakuntala

(7.234). He confesses:

7.250 Memory

chanced to break my dark delusion

& you stand before me in beauty.

The king further

admits his error to Kanva:

7.331 When her relatives

brought her to me after some time, my memory failed & I sinned against

the sage Kanva . . . .

When I saw the ring, I remembered that I had married his daughter.

This is all so strange!

What must seem strange to many of us Western readers is that the king is apologizing to Kanva, not to Sakuntala. In any case, everyone is quickly reconciled: the king, Sakuntala, their son, & Kanva. The play ends with pious invocations to Vishnu & Shiva further illustrating that the play has been a celebration or paean in praise of Dharma. Vishnu sustains our world. Our world is sustained by dharma. Vishnu (including his avatars of Rama & Krishna) is dharma. Shiva burns up karma/maya (illusion) to liberate Atman. Shiva-nataraja is depicted dancing. Both gods suggest that life should be a dance of dharma, as elegantly performed as Kalidasa's play.

Bhakti Poets:

Maha-devi-yakka

#17: What is

it that is being spun “like a silkworm weaving her house”? The parallel

is that the poet is spinning this poem & others like it (the silk)

out of her deepest desire, which is for unity with the divine, in this

case, Shiva:

9

I burn

desiring what the heart desires.

Shiva is often depicted

dancing inside a circle of flames. The flames represent our buring

desires (karma) from which Shiva rescues us by burning up or destroying

our illusory concerns & games. Strangely – but typically Hindu

– our poet recognizes that her longing & her conceptions of the divine

(as Shiva) are not the divine; they are more silk; they are merely human

ideas of what the divine is. As such they are obstacles, idols.

Thus the poet prays for deliverance from her pious ideas!

10 Cut through,

O lord,

my heart’s greed,

& show me

your way out

Inside of being bound

by my ideas. Her greed is the hope to possess the divine.

We cannot possess the divine; we can only hope that it will possess us.

Our conceptions & words wrap us up in a cocoon, like a silkworm.

No matter how elegant or wonderful the cocoon is (silk), it is a projection.

It is us (our ideas), not the divine. We are wrapped up in our ideas.

Ultimately we must give up even our pious [Dharma] ideas of what

the divine is & how to approach it, praying to be delivered from ourselves:

show me

your way out

[of myself]

#114:

This poem illustrates conflicting duties:

1

Husband inside,

lover outside.

I can’t manage them both

Her husband is “inside”

the structure of Dharma. Her behavior towards him is explicitly

codified by Dharma. The lover she wants is hardly another

man. The one she truly loves is God, Shiva, for whom she would do

anything. Thus he beckons to her “outside” of the ritual actions

of simply obeying Dharma. She longs to abandon her social

position as wife & somehow run away with her lover:

4

This world [of Dharma]

& that other [of love],

[I] cannot manage them both.

This is a lyric poem,

expressing the poet’s feelings. Despite what she says, the poet does

manage to live in both worlds. How could she “run away with her lover”?

Obviously she could not in any actual sense, since her beloved is blank:

7

O lord white as jasmine

In south India women get fresh jasmine flowers from the market every morning to put in their hair. The flowers are a kind of perfume. The poet can run away with lover by writing the poem or singing bhajans (Hindu religious songs/poems); & these are as much grounded in our world as in the divine, which is blank or which can be discerned only as a sweet smell.

#119:

A short poem with an obvious message. Bhakti poets repeatedly

express their desire to be enraptured by the divine. This poem expresses

impatience with the divine, saying “come & take me right now!”:

4

let it come right now

#124:

The theme here is also obvious. You can lose material possession,

but not your longing for the divine. Your money can be taken, but

3

can you confiscate

the body’s glory?

The “glory of the

body” is obviously the atman (cf. soul) that cannot be taken, because

it is the source or cause of all life, all being. You can be divested

of every possession:

6 but can you

peel

The Nothing, the Nakedness

that covers & veils?

Atman is not

a specific thing. If it were, it would somehow be a possession in

my mind. In fact Atman is the divine energy that vivifies

the mind. It is “nothing” or blank in the sense of not being construable

as a thing; it is no single thing. Not itself discernible, the Atman

veils & covers itself by producing objects of consciousness.

We could not possess those objects without the sustaining force of the

divine, the:

11 light

of morning,

You fool,

Where’s the need for cover & jewel?

The poet calls herself a fool for slipping into the mistake of conceiving of the divine as an object to be approached with “cover & jewel,” i.e., approached through ritual or prayer. This is foolish because the divine is already operating to vivify you. God already possesses you or you wouldn’t exist.

#283:

The “Handsome One” is, of course, Shiva, who:

2

has no death

decay nor form

no place or side

no end

Again the bhakta

tells us that the divine cannot be conceptualized as an object, or as someone

approached through ritual or prayer:

6

I love the Beautiful One

with no bond [such as Dharma] nor fear

no clan [suggesting caste or varna-dharma]

no land [suggesting pilgrimage to a specific place]

Our poet is

rather impatient with her evidently less handsome husband in this world,

suggesting to her readers that they:

13 Take

these husbands who die,

decay, & feed them

to your kitchen fires!

It is a mistake to suddenly decide that this is political or marital advice about our world of decay. Like every line of every poem, these lines advise us to renounce the objects of this world & turn our attention to the divine. It isn’t your actual husband that you love but the atman in him. The kitchen fire is not cooking another dinner to be offered as another ritual to some object or idol of the divine (such as, your husband who is ideally suppose to act as an idol for your affections). We should all do the reverse, be consumed in the burning love of the divine.

#294:

Another poem of longing for the divine that suggests a paradox. The

paradox is that orthodox religion, that stresses ritual & moral behavior,

is itself an obstacle to an all-consuming mystical experience of the divine.

This is a major theme in both Hinduism & Buddhism. You will also

find it to be a major theme in the Sufi story that we will read.

In the first stanza the poet rejects the objects of love in this world.

In fact they are ugly:

4 face

withered,

body shrunk

1 why do

you talk

to this woman?

Having told her husband

to leave her alone, she also tells her “fathers” to leave her alone.

These would be anyone in authority who could expect her to perform some

duty. She has abandoned such duty:

8

She . . .

has lost the world

lost power of will [to do Dharma]

turned devotee

Becoming a devotee

or a bhakta means not caring what other think about you. Your

behavior is no longer motivated by ego defensiveness. Paradoxically,

it is a kind of adultery, defecting from loyalty to the things of this

world:

12 she has lain

down

with the Lord, white as jasmine,

& has lost caste.

Our text says the bhakta is so enraptured by the divine, that “she is ready to face slander & punishment for breaking the rules by which an Indian woman is expected to live.” Initially you may think this sounds strange. How can the divine entice us to violate morality? Soren Kiergeggard mused on exactly this paradox in regard to Abraham, whom Yahweh prompted to murder his own son, thereby offering Abraham a chance to prove that he was more dedicated to the divine than to his own moral rectitude. Moreover, this portrait of faith, in the figure of Abraham, is shared by Judaism, Christianity, & Islam more than any other element.

Govinda-Dasa:

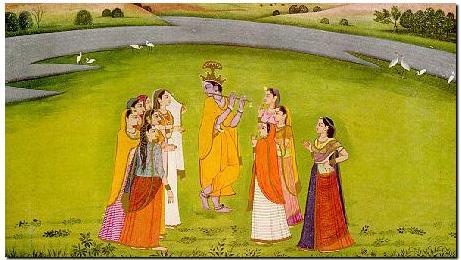

We may again be surprised at the explicitness of the connection between sexual longing & the longing for the divine. Our text says that “God & the human soul desire each other like Radha & Krishna [desire each other]. . . . Far from hindering spirituality, Radha & Krishna’s sensuous apprehension of each other . . . becomes the devotee’s vehicle to a true understanding of God’s nature [as love] & the fullest experience of a relationship of mutual love with him” that disregards moral judgments as profane & ego defensive (p. 1422).

Terror:

This poem illustrates

the emotional price of abandoning moral rectitude:

1

O Madhava, how shall I tell you of my terror?

I could not describe my coming here

4

I trembled:

I could not see the path

precisely because

there is no conventiional path. A path is worn by the feet of many

pilgrims whose (moral) journey defines convention (Dharma).

In contrast:

8

I was alone

But I had the hope of seeing you, none of it mattered

What is the “it”

here? Obstacles to her union with Krishna. What are those obstacles

likely to be? They are likely to be conventional moral expectations.

17 When

the sound of your flute reaches my ears

it compels me to leave my home, my friends,

it draws me into the dark toward you.

Into “the dark”

because the divine has no conventional form, including morality.

The next poem expresses the wild abandon of such mystical love.

When they had made love:

8

Where has my love gone?

O why has he left me alone?

And she writhed on the ground in despair,

only her pain kept her from fainting.

Mirabai:

Although she lived 500 years ago, Mirabai continues to be immensely popular in north India. Our texts says that “Mira’s songs are sung all over India” (1425). “The central theme of Mira’s poetry is that of breaking away from husband & family to engage in an erotic, romantic relationship with Krishna.”

#37:

This poem refers to the Holi festival “in which men & women

spray each other with colored water or throw colored powder [rung] on each

other” (1426). Having experienced this festival, I can you that it

is fun. In large part, the festival invites us to suspend our usual

sense of duty & obligation. Instead of being deferential &

respectful to your boss, you are allowed to rub rung (color) on

his head & face or squirt his white shirt with brightly colored dye.

After hours of this play, you are quite the site. Mira uses the metaphor

of rung or dye to suggest that Krishna has rubbed his color or essence

on her so that she is:

2

colored with the color of my Lord

#42:

This poem is certainly direct:

1. Life

without Hari [Krishna] is no life

Consequently,

the poet is determined to escape conventional life in order to be enraptured

with the divine:

6

A guard is stationed on a stool outside,

& a lock is mounted on the door,

How can I abandon the love I have loved

in life after life?

#82:

This poem alludes to the monsoon rains when one is stuck in the house &

can only look at the rain:

6

Rain & rain two hours long

12

I stubbornly stand at the door

Waiting for Krishna

to come like the rain & drench her in his love.

#166:

Another poem that suggests the unconventional experience of bhakti:

2

Murali [Krishna] snatches away my [ordinary] mind;

My sense cut loose from their [habitual] moorings--

6

lost even the power to think

8

Come quick, & snatch away my pain [of longing]

#193:

1

Let us go to a realm beyond going

Obviously this destination

is not of this world; a place where we can float in a “lake of love” (5).

This is a state of mind:

13

where the love of the Dark One [Krishna] comes first

& everything else is last

* * *

| Questions |