Unit 6

English 203:

Literature of the NonWestern World

|

Unit 6 |

English 203: Literature of the NonWestern World |

| Introduction | .Explication | Questions | Review |

Reading:

739-811,

Sakuntala

1411-29, Bhakti Poets

| BhaktiPoets |

Introduction:

Sakuntala:

At the end of the previous lesson I suggested that Kalidasa's play resembles the Ramayana because both pieces are so formal. Unfortunately we cannot fully appreciate Sakuntala by reading the play. Like great opera Sakuntala offers a lavish spectacle of gorgeous sets, sumptuous costumes, dance, song, elegant poetry -- all wrapped up in an uplifting religious homily.

Greek tragic drama taught morality by illustrating negative moral examples. The audience left the play relieved not to be as obsessional, proud, or unrestrained as Medea, Antigone or Agamemnon. The medieval cathedral offers a better parallel for Hindu theater. They are both designed to give people a taste (rasa) of a better, higher, more beautiful life. The play features formal & elegant dance as an illustration of how life ought to be lived. Our text says that the shastra on dance, "the Natyasastra treats dance, music, & poetry as aspects of dramatic action in the unified aesthetic of rasa (taste), preserved in the major traditions of classical dance [that continue to be staged] in India today" (746). Rasa illustrates the Hindu recognition that wisdom comes from taste or experience, not theory. You can tell someone everything there is to know about honey, e.g., but they will never know what it is until they taste it.

Hindus should leave a production of Sakuntala regretfully, somewhat sad that our world suffers in comparison to the world of Sakuntala. The moral lesson is clear. If we want to live in Sakuntala's world, we must be as restrained & refined as Rama. Kalidasa does offer a mildly negative moral illustration. The suffering (which is almost negligible compared to the twisted passion of Greek drama) is caused by impetuosity. The king secretly marries Sakuntala before asking her father or guardian. Sakuntala gives herself to the king before asking her father. Our text says, "At first each [person] acts impulsively, moved purely by passion. In the end, each is refined by duty [dharma] & chastened by suffering" (747). However, our text also recognizes that the king, Sakuntala, & her father "are types, not individuals." Consequently we are not deeply involved with their lives. We neither love nor hate them. We are charmed by both them & by the lavish ritual performance of the play.

Bhaktas:

Kalidasa wrote his play in classical Sanskrit. Again the analogy of Western opera helps explain it. How many of us understand Italian or German? Operas continue to be sung in these languages that few in the audience can understand. Now imagine that the opera is sung in something like Virgil's Latin. Many Catholics used to attend lavish Cathedral rituals, especially to celebrate Christmas & Easter, that were entirely conducted in Latin amid the smells of exotic & expensive incense, sumptuous costumes, & almost divine architecture. Sakuntala belongs to that rarified world created by the best that several arts can produce.

Bhakti poetry is a peasant art. It offers nothing but simplicity & sincerity. The bhakta poet has nothing or has given up everything in this world, like St. Francis, in order to taste the divine. Unlike everyone (author, actors, dancers, & audience) in Sakuntala, who were among the best educated, bhaktas had no education. Kabir was the son of a Muslim weaver. Mirabai was a very unconventional, nearly crazy, wife.

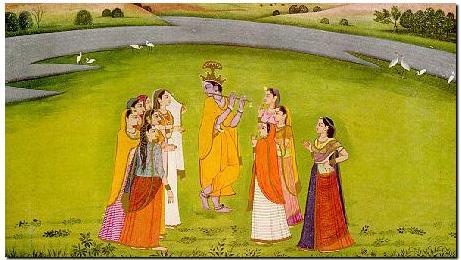

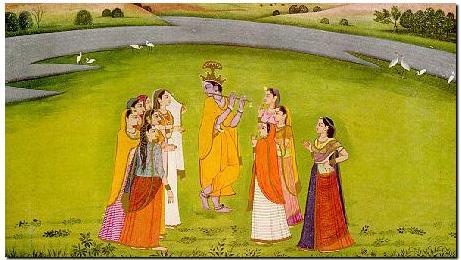

You will recall that bhakti is a marga, a path to moksha (liberation) that relies on nothing but emotion. Love God deeply & totally, & God will accept you. Every other concern is a distraction that obscures the goal & reduces your chances of reaching it. Thus the poems all illustrate the same theme: be obessional & fanatic in the love of Krishna, Shiva, Devi, or some other pet name for the beloved.

That

brings us to another fairly unfamiliar religious metaphor & technique:

sex. In Hinduism the divine never punishes. We punish ourselves

by our anxiety & fear & petty concerns. God is always alluring.

The prophetic religions often seem to operate more by threat than by enticement

& allure. The major exception was the thousand year long medieval

flirtation with the goddess of love, the Virgin Mary, which is not entirely

historic. Mexican Catholicism is arguably more centered on the Virgin

Mary than on Calvin or Paul's notion of Christ. Certainly this is

true about bhakti or devotion. The current Pope is inclined

to declare that Mary is the co-redemptress of humanity, meaning that Mary

is the sole dispenser of salvific grace earned by Christ.

In any case, the bhakti convention characterizes the human soul

as a love-sick girl or young woman who will sacrifice anything, including

moral pride, to experience (sexual) union with the divine. Govindadasa's

3 poems all use this metaphor, which suggests that the love of God is like

sexual love but better:

p.

1424 When the sound of your flute reaches my ears [Krishna]

it compels me to leave my home, my friends,

it draws me into the dark toward you

Typically the Western parallel about giving up everything for God relies on violence. Abraham gives up even his moral status of being righteous. He doesn't care if people think he is a child murderer. What could be worse? He cares only & exclusively for El Shadai as he calls God (meaning the god of the rock). In the typically female outlook of Mother India, Govindadasa & Mirabai do not care if they are thought to be whores ("Husband inside,/ lover outside./ I can't manage them both") or simply insane ("They thought me mad for the Maddening One"). All they care about is union with the divine.

Kabir

mocks gnostic asceticism:

Brother,

if holding back your seed [i.e., celibacy]

Earned

you a place in paradise,

eunuchs would be the first to arrive (Hawley 35)

Lastly,

I should say something about caste, poverty & a kind of Marxist class

conflict between the lowly bhaktas & the very aristocratic image

of Rama & the proud Brahmin priests who often seem to spend much of

their lives trying to avoid pollution that rises from the touch or even

the sight of pariahs. Bhaktas are not interested in the things

of this world. They have no politics, because all politics is illusory

(maya). In his interesting book, The Songs of the Saints

of India, John Stratton Hawley says that the bhakta's:

p.

17 vision seems to be not so much that God desires to

reform society

as that He transcends it utterly, & that in the light of the experience

of sharing in God, all social distinctions lose their importance.

I suppose I should not have been surprised, but I was, to find that the songs of Kabir, Sur Das, Mirabai, & other bhaktas continue to be popular in India, easily available in music stores on cassette & CD. If you find bhakti interesting, you may wish to read my first person essay on it & India.

To

read "God with an Elephant Head" click here: ![]()

Click to go to the next section:

| Explication |